Toxic Deception: The Navy’s Playbook of Denial - from the Chesapeake Bay to Red Hill, Hawai’i

By Pat Elder

October 14, 2025

The Oily Waste Disposal Facility (OWDF) on the southwest side of Red Hill is the site of dangerous PFAS contamination.

The Navy has released new groundwater data revealing the extent of PFAS contamination caused by the catastrophic 2022 spill of aqueous film-forming foam concentrate at the Red Hill Fuel Storage Facility. Among the numerous datasets published by the Navy and its contractors, this one stands out: PFAS levels in shallow monitoring wells are several orders of magnitude higher than those detected in deeper zones. This stark vertical contrast confirms what many suspected from the start — that the Navy’s earlier assurances concealed the true severity of contamination following the foam concentrate spill.

The Navy maintains that the Red Hill aquifer is safely confined by a complex network of subsurface volcanic rock and soil beneath the fuel tanks. According to this view, interbedded layers of low-permeability material limit the downward movement of water and contaminants, forming a natural barrier that isolates the contaminated shallow zones from the deeper basal aquifer. This narrative implies that the aquifer remains protected because any leaked fuel, foam, or vapors would be trapped or slowed by these confining layers—despite the fact that the tank floors lie only about 100 feet above the island’s primary source of drinking water.

In contrast, the Honolulu Board of Water Supply (BWS) rightly contends in its landmark lawsuit against the United States that the Red Hill aquifer is not a confined system, but a highly vulnerable sole-source aquifer that directly provides drinking water to the people of Oʻahu. The BWS argues that the geology beneath Red Hill is fractured, permeable, and riddled with interconnected pathways through which contaminants can readily migrate. They underscore that the aquifer lies just about 100 feet below the massive underground fuel tanks, that no alternate source of comparable quality or capacity exists, and that contamination of this aquifer would jeopardize the island’s only sustainable supply of fresh water.

There is no moral ambiguity here—there are good guys and bad guys in this struggle. On one side stand those fighting to protect the island’s lifeblood; on the other, a military machine hiding behind secrecy and denial. What we’re witnessing is not just negligence, but a calculated evasion of responsibility—a familiar playbook the Navy has used around the world. Instead of confronting the contamination poisoning Oʻahu’s water, they cloak the truth in technical jargon and bureaucratic delay. Behind that façade lies environmental ruin, broken trust, and an unfolding tragedy of human illness and cancer that no community should ever have to endure.

In the Navy’s groundwater monitoring program, cluster wells are designated as either “A” or “B.” The “A” wells reach deep into the earth, while the “B” wells are shallow. The deep wells, drilled roughly 150 to 600 feet below ground, tap the aquifer that supplies Oʻahu’s drinking water. The shallow wells, by contrast, extend only 25 to 50 feet beneath the surface and are not used for consumption. It makes intuitive sense: gravity and time pull contaminants downward, allowing carcinogens to slowly sink into the bosom of the earth.

Yet nearly all of the data the Navy has chosen to highlight come from those deeper “A” wells—where PFAS and other toxins appear at much lower levels. The Navy points to these results as reassurance, emphasizing that the highly contaminated shallow groundwater is “not used for drinking water.” It’s a selective truth—technically accurate, yet profoundly misleading.

And so, the real question becomes this: how easily can contamination travel from the heavily polluted shallow aquifer into the deeper one that provides our drinking water? The Navy would have us believe that such movement is unlikely—a claim they have repeated not only here, but at the Naval Research Laboratory – Chesapeake Bay Detachment and other contaminated sites across the country.

Their official explanation reads: “Below the shallow groundwater is a layer of soil and rock that limits the downward flow of the shallow groundwater, segregating it from the deep groundwater.”

But this framing is deceptive. It relies on a convenient fiction of geological separation - a supposed natural barrier that regulators and independent scientists have repeatedly found to be fractured, leaky, and unreliable.

The Navy wants us to believe there’s a sturdy barrier of soil and rock holding the poisoned shallow water safely above the island’s main aquifer. But that’s a myth. The truth is the ground beneath Red Hill is more like a leaky layer cake—cracked, fractured, and uneven. That thin band of rock may slow the flow of water for a while, but it can’t stop it. Every fracture, every thinning seam becomes a doorway for contamination to move downward, inch by inch, toward the very water we drink. We’re already seeing the warning signs: PFAS and fuel compounds showing up deeper and deeper underground. This isn’t containment—it’s a countdown. It’s only a matter of time before the poisons now sitting in the shallow zone flood the wells that sustain life on Oʻahu.

The EPA and the Hawaiʻi Department of Health have repeatedly warned that the Navy’s groundwater models are riddled with gaps and blind spots. They’ve questioned the Navy’s entire conceptual understanding of how water actually moves beneath Red Hill—through dikes, fractures, and uneven layers of volcanic rock that defy neat, textbook explanations. Given this fractured, unpredictable geology, it is reckless to pretend there’s a single, uniform “barrier” protecting the aquifer. The science doesn’t support it, and neither do the facts on the ground.

“The Navy and the Defense Logistics Agency have expended considerable effort to further knowledge and understanding of the complex subsurface around the Facility since 2015, however, the resulting models in the Groundwater Flow Model Report do not reflect site specific data and associated heterogeneity with sufficient accuracy to provide confidence in model predictions.”

=====================================================================================

Almost immediately, the EPA and the State of Hawaii Department of Health set the record straight, although they are doing little to actually change the Navy’s behavior.

Before we dig into Red Hill’s data, we should recognize the pattern. The Navy has been running this same play across the country—hiding behind “protective layers” while contamination seeps deeper, poisoning communities from Maryland to Hawaiʻi.

The Naval Research Laboratory – Chesapeake Bay Detachment is located 40 miles southeast of Washington, DC.

The Navy has been resorting to the same shenanigans in Maryland since at least 2017—using the Restoration Advisory Board (RAB) as a one-way conduit for disinformation rather than genuine public engagement. It was absurd then, and it’s worse now. Private wells drawing from the supposedly “protected” lower aquifer along the banks of the Chesapeake Bay were already showing PFAS contamination, yet the Navy insisted everything was under control. Several dozen Marylanders attended an online RAB meeting five years ago. They submitted thoughtful questions in advance—only to watch the Navy screen them, cherry-pick what to answer, and skillfully dodge any real discussion. It was theater, not transparency. The Navy refused to answer questions challenging their insistance that the surficial aquifer was contained.

The 2017 Final Sampling and Analysis Plan for Perfluorinated Compounds in Groundwater at the Naval Research Laboratory – Chesapeake Bay Detachment became the Navy’s blueprint for evading accountability for PFAS contamination nationwide. In that document, the Navy claimed that private wells north of the research lab were “believed to be screened in the Piney Point Aquifer,” which lies beneath a “laterally continuous and fully confining” layer of sediment. It was a deliberate misrepresentation. The so-called confining unit was neither continuous nor secure—and the contamination in nearby private wells proved it.

In other words, the state told the Navy plainly: you can’t claim the aquifer is protected unless you prove it. Instead of performing the tests, the Navy refused—saying it would not “support pump tests should this increased risk of potential contamination from one aquifer to another.”

That logic is breathtaking in its cynicism: the Navy invoked the possibility of contamination between aquifers as its reason for not testing whether such contamination was already occurring. The pattern was set. Across the country, the Navy has used the same defense—asserting the presence of “confining layers” to assure the public that deeper drinking-water aquifers are safe, even as PFAS spreads through the shallow zones above them. Don’t worry, be happy, they say.

And so, it’s essential to look at a few examples—other bases where this same script is playing out.

NAS Whidbey Island (Ault Field), Washington

At Whidbey Island’s Ault Field, the Navy again insists that a “lower confining unit” separates shallow and deep groundwater, supposedly shielding drinking-water aquifers from PFAS contamination. But Washington State’s own geologic compendium contradicts that claim, noting plainly that “the presence of a confining layer (aquitard) has not been confirmed directly.”

Once again, the Navy leans on an unproven barrier—an assumption, not evidence—to downplay the risk of contamination moving into the island’s deeper water-bearing zones.

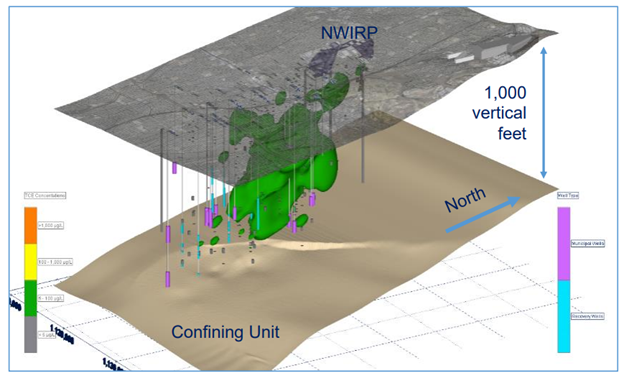

Bethpage/Northrop Grumman–Navy Plume (former NWIRP), Long Island, New York

At Bethpage, the Navy claims that the “Raritan clay” forms a protective confining unit, sealing off the deep Lloyd Aquifer from the massive PFAS- and solvent-contaminated Magothy plume above. In Navy presentations—such as Slide 36 of the Bethpage RAB minutes—an artist’s cross-section depicts a thick, uniform clay barrier separating the shallow and deep aquifers.

Slide 36 Bethpage RAB Minutes

New York State regulators reject this picture. In its Feasibility Study Report (April 3, 2019), the Department of Environmental Conservation (DEC) states: “Within the Magothy aquifer, lenses of low permeability clay, silt, and sand are abundant. These lenses are not necessarily continuous and have a significant influence on the movement of both groundwater and the site contaminants.”

In other words, what the Navy calls a solid wall of protection is, in reality, a patchwork of discontinuous layers that allow contamination to migrate—precisely the conditions that have enabled the Bethpage plume to expand for decades beneath Long Island’s drinking-water supply.

The New York State Department of Environmental Conservation Feasibility Study Report, Bethpage (April 3, 2019), disagrees. The DEC acknowledges that “Within the Magothy aquifer, lenses of low permeability clay, silt, and sand are abundant. These lenses are not necessarily continuous and have a significant influence on the movement of both groundwater and the site contaminants.”

Naval Base Kitsap – Keyport & Bangor, Washington

At Naval Base Kitsap, the Navy describes a neat geologic separation between aquifers. According to its reports, “boring logs from the initial construction of the Keystone Hill well in 2008 are similar to neighboring OLF Coupeville, with silty sand and gravel from the surface to 133 feet below ground surface. A seven-foot-thick confining layer of silty clay from 133 to 140 feet separates the overlying sands and gravels from the underlying fine sand with trace gravel.”

Yet the EPA offers a far less reassuring view. The agency states that an unconfined upper aquifer is present throughout most of the area—meaning groundwater can move freely through the subsurface with little restriction.

Once again, the Navy portrays a clean geological division that regulators say doesn’t actually exist. The so-called “confining layer” is more wishful thinking than physical reality, and it leaves the region’s drinking water far more vulnerable than the Navy admits.

Safe waters?

Navy – 2022 - Safe Waters AFFF Release Response

Groundwater Samples were collected December 2022 - December 2023 from monitoring wells surrounding Red Hill. They were taken from 223 to 253 below the ground surface.

6:2 FTS 269 ppt

PFBA 48.0 ppt

PFPeA 13.0 ppt

PFHxA 7.10 ppt

PFHpA 2.90 ppt

PFNA 2.20 ppt.

PFOA 1.70 ppt

PFOS 1.40 ppt

PFHxS 1.40 ppt

346.70 ppt of Total PFAS

223–253 feet below ground surface.

No exceedances of Hawaii Environmental Action Levels, (EALs).

They drilled deep—down at least 223 feet - and released data showing relatively low PFAS concentrations, carefully crafted to calm public concerns. It was a familiar move in the Navy’s playbook: test the deepest wells, publish the cleanest numbers, declare victory, and hope the issue goes away. The response followed a well-rehearsed pattern of obfuscation—highlight the relativle “safe” results from the deep aquifer while ignoring the contamination festering closer to the surface. Actually, the 6:2 FTS results were alarming. 6:2 FTS is more mobile than the long-chain “classic” PFAS (like PFOS and PFOA).

The Navy unveiled this next set of extraordinarily low results.

Well RHP02 is 145 feet below ground surface; Well NMW32 is 210 feet below ground surface. The PFOS and the PFOA from well NMW32 exceeded the Hawaii Environmental Action Level of 4 ppt.

- Naval Facilities Engineering Systems Command Pacific JBPHH HI Per- and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances Delineation Baseline Groundwater Wells Investigation Report Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility JOINT BASE PEARL HARBOR-HICKAM O‘AHU HI November 27, 2023.

Now let’s turn to the most recent data—the Navy’s PFAS Data Summary No. 1 for the Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility, Joint Base Pearl Harbor–Hickam, Oʻahu, Hawaiʻi, dated July 2025.

These results come from shallow monitoring wells, located roughly 25 to 50 feet below the ground surface—the very zone where contamination first seeps into the subsurface before gravity and time carry it downward. This is where the story of the spill’s impact is told most clearly, unfiltered by depth or delay.

Figures are in parts per trillion.

OWDFMW03B Total PFAS 19,278.996

OWDFMW03B Total PFAS 22,088.493

OWDFMW04A Total PFAS 81.58

OWDFMW05A Total PFAS 385.307

The Navy’s wells are divided into two types: the deep “A” wells, and the shallow “B” wells. This new dataset marks the first time we’ve seen PFAS results from the shallow groundwater—the zone closest to the spill and most vulnerable to contamination. The numbers are alarming. These higher concentrations won’t stay put forever. It’s only a matter of time before they migrate downward into the deeper aquifer that supplies drinking water to Oʻahu.

So, what exactly is the Navy telling us about Red Hill—and what are they leaving out? Let’s break it down.

The Navy points to the CERCLA process—the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act, better known as the Superfund law—as the framework guiding its cleanup at Red Hill. Under this program, the Navy has launched what it calls a Remedial Investigation (RI) at the Red Hill Bulk Fuel Storage Facility.

But the process has become a bureaucratic quagmire. The CERCLA system—slow, fragmented, and perpetually underfunded—moves at a crawl while contamination spreads and communities wait. The Navy hides behind this red tape, knowing full well that time and community exasperation are their greatest allies. Meanwhile, Congress continues to cut budgets, and the powerful corporate and military interests behind these operations remain untouched. They count on the public not connecting the dots—between the contamination beneath their feet - and the cancers, immune disorders, and other diseases that follow in its wake.

It is the very concept of a “Remedial Investigation” that is most troubling. The Navy describes the “RI” as a necessary step to “better understand” the extent of contamination and to develop a plan for cleanup. But that notion borders on absurdity when we’re dealing with PFAS chemicals—compounds that are virtually indestructible and already pervasive in soil, water, and bloodstreams around the world. How can there be a cleanup plan for something that doesn’t break down? There isn’t one.

Oʻahu is in serious trouble. The first and most urgent step should be to ban the use of PFAS entirely, except for a tiny handful of truly essential applications. But this, of course, isn’t part of the Navy’s game plan. Instead, the military hides behind the rhetoric of “national security,” insisting that continued PFAS use is vital to defense operations—and that Hawaiʻi must learn to accept this toxic reality.

When states have dared to sue the Department of Defense for PFAS damages, the Pentagon’s lawyers have invoked sovereign immunity, claiming the government cannot be held liable. In effect, they are asserting the right to contaminate in the name of national security—to poison with impunity while the people of Hawaiʻi bear the cost in sickness, fear, and the slow death of their water.

Please support my research! Thank you for your help with our testing at Fort Ord and in Oahu, Hawaii. I will have a full report once I receive all of the data. I promised my wife Nell I won’t spend any more of our retirement money. Access to news outlets, membership fees, email distribution costs, and other expenses top $400 monthly. The photo shows the daily foam gathering on our beach from the Navy base across the creek. Quite literally, this problem came to us. The Navy has poisoned our water, fish, crabs, and oysters. Contribute here: https://worldbeyondwar.org/support-military-poisons/