An analysis of PFAS at Kahuku Training Area, Makua Military Reservation, and Kawailoa-Poamoho Training Area

By Pat Elder

January 26, 2026 Part 3 of a 6-part series.

U.S. Army Hawaiʻi has responsibility for training activities on Oʻahu, including those conducted on state-leased lands. Major General James (Jay) Bartholomees III is the Senior Commander for U.S. Army Garrison Hawaiʻi.

On August 3, 2025, the U.S. Army signed a legally binding Record of Decision governing the future of its leased training lands on Oʻahu. Under the decision, the Army announced it will relinquish 4,390 acres at the Kawailoa–Poamoho Training Area and 782 acres at the Mākua Military Reservation, while retaining approximately 450 acres of the 1,150 acres currently leased at the Kahuku Training Area. In total, the Army will return 5,872 acres of state land, long used by Army units and other military entities—including the U.S. Marine Corps and the Hawaiʻi Army National Guard—marking a significant contraction of the military footprint on the island.

The legally binding Record of Decision has not been reported by the media in Hawaii.

The Army’s Strategy

The Army appears to be pursuing a single, integrated strategy designed to preserve what it values most while quietly shedding land that has become politically and operationally costly. Its decision not to renew leases at Mākua Military Reservation and Kawailoa–Pōamoho Training Area, combined with plans to reduce the footprint at Kahuku Training Area, reflects a deliberate consolidation rather than a genuine retreat.

On Oʻahu, the Army’s training areas have long been a source of conflict. Decades of litigation, cultural access disputes, wildfire risks, and unexploded ordnance have hardened local opposition. Persistent and unresolved contamination—particularly PFAS—has further undermined any credible claim that continued military use is compatible with public safety or environmental protection. Community groups and environmental organizations have applied sustained pressure, and from the Army’s perspective, the political cost of maintaining these leases now outweighs their training value.

That reality was brought into sharp focus by the rejection of the Army’s poorly executed Final Environmental Impact Statements for both the Pōhakuloa Training Area and the Oʻahu training lands. While the outcome should not have come as a surprise, it clearly unsettled Army leadership, signaling that the longstanding practice of minimizing impacts and deferring accountability is no longer being accepted at face value.

==================

The Final Environment Impact Statement for the three Oahu bases is separated into 4 volumes and comprises 4,774 pages:

Army Training and Retention of State Lands at Kahuku Training Area, Kawailoa-Poamoho Training Area, and Makua Military Reservation Island of O’ahu Final Environmental Impact Statement

VOLUME I: FEIS DOCUMENT May 2025, 624 pages

VOLUME II: APPENDICES A-L May, 2025 1,440 pages

VOLUME III: APPENDIX M-1 May, 2025 1,430 pages

https://files.hawaii.gov/dbedt/erp/Doc_Library/2025-05-23-OA-FEIS-Army-Training-Land-Retention-on-Oahu-Vol-3-of-4.pdf?utm_source=

VOLUME IV: APPENDIX M-2, May, 2025 1,280 pages

https://files.hawaii.gov/dbedt/erp/Doc_Library/2025-05-23-OA-FEIS-Army-Training-Land-Retention-on-Oahu-Vol-4-of-4.pdf

========================

The Army must not be permitted to renew its lease of 450 acres at the Kahuku Training Area. Its long record of environmental mismanagement contradicts its relentless public-relations messaging about “stewardship.”

Kahuku Training Area’s record is characterized by years of chronic environmental damage that federal and state agencies have repeatedly addressed. Official documents acknowledge chronic soil disturbance and erosion, habitat degradation, wildfire risk, and impacts to sensitive and endangered species. These are documented impacts arising from routine training activities. The State of Hawaiʻi’s recent rejection of the Army’s Final Environmental Impact Statement only underscores a long-standing trust gap, confirming that the Army has failed to adequately disclose, analyze, or mitigate the environmental consequences of its presence at Kahuku. This history makes clear that renewing the lease would reward poor stewardship rather than protect public lands.

All of this sets the stage for the Army’s top priority: the Pōhakuloa Training Area on the island of Hawaiʻi. In the meantime, the Army is seeking a free ride, attempting to evade enforceable reporting and cleanup obligations at its three Oʻahu installations for a wide range of contaminants, especially PFAS. Because PFAS is widespread, persistent, and extraordinarily expensive to fully investigate and remediate, the Army, absent a moral compass, has every incentive to minimize disclosure and delay accountability.

The Army’s legacy on state lands on Oʻahu includes some of the most toxic chemicals and hazardous conditions known to environmental science. Although this report focuses on PFAS, it must be understood as only one component of a much larger contamination footprint that includes chlorinated solvents, explosive residues, radioactive materials, petroleum byproducts, and active and abandoned munitions areas, such as:

· Improved Conventional Munitions (ICM)

· Trichloroethylene (TCE)

· Perchloroethylene (PCE / Tetrachloroethylene)

· Perchlorate

· RDX, HMX, and TNT residues

· Depleted uranium

· Live-fire and demolition areas

· UXO and munitions disposal zones

· Vinyl chloride

· Benzene

========================

Final Environmental Impact Statement

The Army’s Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) for state-owned training lands on Oʻahu deliberately sidesteps PFAS contamination, arguably the most consequential environmental liability associated with military operations. PFAS compounds are highly carcinogenic, environmentally permanent, and extraordinarily expensive to remediate. Their exclusion from the FEIS is not accidental; it allows the Army to evade cleanup obligations and obscure long-term risks to public lands and water resources. Allowing this omission to stand would legitimize a fundamentally incomplete and misleading environmental record.

In May 2025, the Hawaiʻi Board of Land and Natural Resources voted 5–2 to reject the U.S. Army’s Final Environmental Impact Statement for three installations on Oʻahu: Kahuku Training Area, Kawailoa-Poamoho Training Area, and the Mākua Military Reservation. In a separate action, they also voted to reject the Army’s Pohakuloa Training Area FEIS on Hawaiʻi Island.

The Hawaiʻi Board of Land and Natural Resources concluded that the Army’s environmental review failed to adequately address long-standing environmental and public-trust concerns. They said the Army failed to adequately address long-documented environmental degradation associated with decades of military training. This was a clear regulatory rebuke. Without an accepted FEIS, the Army had no legal basis to renew or continue these leases under state law.

The Hawaii Board’s 2025 decision represents a precedent-setting example of a U.S. state using its own environmental review authority to challenge the Army’s environmental analysis to block continued occupation of military training lands. Hawaii is setting a precedent. The Aloha State’s actions will influence future state–federal land and environmental disputes.

The following statement represents the totality of the Army’s position expressed in the FEIS on PFAS contamination at the three Oahu installations:

“Per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS), a group of emerging contaminants, are associated with the historical use of aqueous film-forming foam on military installations. The Army conducted a Preliminary Assessment/Site Inspection (PA/SI) to evaluate sources of PFAS other than aqueous film-forming foam, (AFFF), including metal plating operations, photo-processing areas, wastewater treatment plants, pesticides, and landfills. The purpose of the PA/SI was to identify areas of potential interest where PFAS-containing materials were used, stored, and/or disposed of, or areas where known or suspected historical releases to the environment occurred. The PA/SI concluded that there were no areas of potential interest for KTA, Poamoho, or MMR; therefore, no further PFAS investigations at these installations are warranted.”

The DOD has spent $50,000 investigating PFAS at the Kahuku Training Area and has no plans to allocate further funds after FY 2025. DOD, 3/31/25. That was easy.

Kahuku Training Area

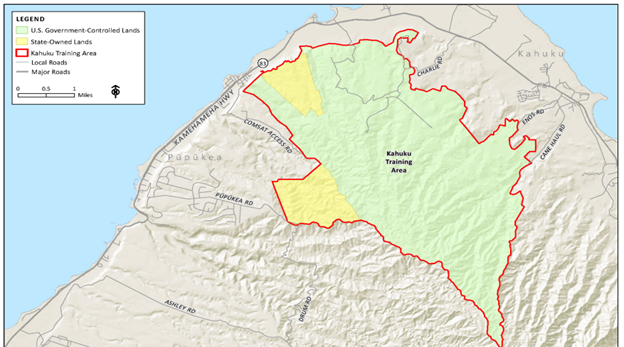

The Army is relinquishing the parcels shown in yellow.

The Kahuku Preliminary Assessment is lumped in with five other Army installations that were all found to be free of PFAS. The scant 76-page report identifies no “areas of potential interest” for PFAS contamination at any of these six bases:

Kahuku Training Area, Makua Military Reservation, Dillingham Military Reservation, Kipapa Ammunition Storage Site, Kunia Field Station, and Waikakalaua Ammunition Storage Tunnels

The Kawailoa-Poamoho Training Area shares its preliminary assessment with Schofield Barracks and was also found to be free of PFAS.

The Kahuku Training Area is located on the north shore of Oʻahu, approximately two miles west of the town of Kahuku. The installation encompasses roughly 9,480 acres, most of which lie within the Koʻolau Mountains, with the Pacific Ocean located about one mile north of its northern boundary. More than half of KTA is used for ground maneuver training. Of the approximately 1,150 acres of state-leased land within KTA, the Army plans to retain about 450 acres while relinquishing roughly 700 acres back to the State of Hawaiʻi.

Helipads/Landing Zones at Kahuku Training Area

Although Kahuku does not have a defined cantonment area, the installation does have several compounds to support Army-related operations that likely use PFAS. The installation has designated helipads/landing zones for military helicopters and parachute drop zones for personnel and equipment. The Army says Kahuku will presumably continue to be used as a training area, as well as for recreational activities, in the future.

There are many well-documented examples where PFAS/AFFF use is tied directly to helicopter landing zones, helipads, or helicopter crash/response sites at Army installations. Examine the PA/SI of the Pohakuloa Training Area (PTA) on Hawaii Island. During the Landing Zone Rob helicopter crash in the late 1990’s AFFF was used during a response to a CH-53 helicopter crash at LZ Rob. 3,000 gallons of water and 90 gallons of AFFF were used in response efforts.

Helicopter landing zones and helipads are well-documented sources of PFAS contamination at Army installations nationwide.

Consider the Preliminary Assessment for PFAS at Carlisle Barracks, PA. The Army initially included the “Helipad – AFFF Equipment Testing Area” as a PFAS “Area of Potential Interest” but failed to test groundwater, surface water, or soil for the chemicals and ended the investigation.

Fort Lee, VA - Table ES-1 from the PA/SI for PFAS at Fort Lee, VA identifies a helicopter pad site as part of a Former Firefighter Training Area and describes foam training and testing by the helipad. A parking lot near the helipad was used for foam training. The investigation was halted.

Fort Ord, CA - The Army Helicopter Defueling Area at Fort Ord, California is highly contaminated with PFAS. The groundwater at 99.5 feet below the surface contained 19,000 ppt of PFOS, 1,340 ppt of PFOA, and 47,555 ppt of Total PFAS Those tests were conducted on 11/30/22. Fort Ord’s helipad PFAS contamination confirms that PFAS released at helicopter pads does not remain shallow or localized; it migrates vertically through the vadose zone and laterally within aquifers over time.

Kahuku Training Area contains the same operational features—helipads, landing zones, parachute drop areas, and emergency response activities—that have been documented sources of PFAS contamination at other military installations. Despite this well-established pattern, the Army has failed to meaningfully evaluate these features at Kahuku.

The Fort Ord data demonstrate that PFAS released at helicopter pads does not remain shallow or confined; it migrates downward into groundwater and outward through aquifers over time. By continuing to use Kahuku for aviation and training activities while omitting PFAS analysis, the Army is ignoring known contamination pathways and repeating a pattern of premature closure seen at Carlisle Barracks and Fort Lee. This failure to investigate predictable PFAS sources renders any claim of environmental stewardship at Kahuku incomplete, misleading, and scientifically indefensible. Go away, Army.

Kahuku Training Area, Kawailoa-Poamoho Training Area, Mākua Military Reservation, and the Pōhakuloa Training Area on Hawaiʻi Island, have all supported sustained helicopter operations under U.S. Army control since the 1960s.

Assessing PFAS risk at the Army’s training areas must focus on AFFF use at helicopter landing, fueling, and drop zones such as Perry Landing Zone, Johnson Landing Zone, Water Tank Hill Landing Zone, and Kane’s Drop Zone at Kahuku Training Area. According to the Army’s 2021 Environmental Impact Statement Preparation Notice for the Training Land Retention Project, all of these likely contaminated sites are located on federally owned land at Kahuku. While the State of Hawaiʻi is set to receive certain parcels back from federal control, the most heavily used and potentially contaminated training areas will remain in federal hands—reinforcing the calls of environmentalists and community advocates that the Army should withdraw entirely and return all lands.

The Army’s recent Final Environmental Impact Statement doesn’t mention any of it, and neither does the Preliminary Assessment for PFAS.

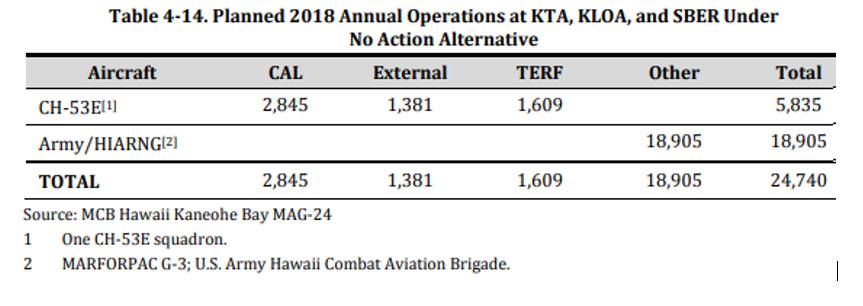

Table 4-14 below shows nearly 25,000 helicopter operations each year across Kahuku, Kawailoa, and the Schofield East Range. Collectively, these takeoffs, landings, refueling, and maintenance activities represent a significant and recurring source of PFAS releases. PFAS use at helicopter facilities is not limited to emergency firefighting foams; it also occurs during AFFF training exercises and through routine aviation operations involving PFAS-containing degreasers, lubricants, hydraulic fluids, chrome-plated components, gaskets, seals, and other maintenance materials. Over decades of continuous use, these routine operational pathways create predictable and cumulative PFAS contamination at landing zones and support areas.

Final Environmental Impact Statement for basing of MV-22 and H-1 Aircraft in support of III Marine Expeditionary Force (MEF) Elements I Hawaii, June 2012

While these operations are distributed among the three areas, Kahuku Training Area supports a substantial share of this activity because it contains the designated helicopter landing zones and the sole parachute drop zone, concentrating repeated ground-contact aviation operations at a small number of sites.

The table shows that Marine Corps CH-53E aircraft alone account for more than 5,800 annual operations, while Army and Hawaiʻi Army National Guard helicopters account for nearly 19,000 additional operations.

At KTA, aviation support operations involve up to four attack helicopters in teams of two, typically maneuvering, providing observation and attack support to ground forces while another helicopter team is rearming and refueling. Virtually all Army refueling operations are accompanied by AFFF delivery systems.

These operations involve repeated ground contact, prolonged hovering, and external loads. These are activities that require on-site crash and fire response capability and have relied on AFFF-based firefighting agents.

Despite years of public assurances, PFAS-based AFFF has not been eliminated from military installations. EPA regulations allow continued use for emergency response, and congressional waivers have repeatedly delayed the phase-out, meaning PFAS-laced foams remain in service wherever aviation fire risk persists.

Table 4-14 confirms that Kahuku’s helicopter landing zones and its drop zone were used not only by Marine Corps aircraft, but also routinely by Army and Hawaii Army National Guard units, meaning that multiple service branches repeatedly operated over the same small patches of land. As a result, any historical releases of fuel, foam, rinse water, or wash-down residues would be expected to accumulate at these locations, rather than being evenly distributed across the broader training area.

The Army’s Environmental Impact Statement for the Kahuka Training Area does not include site-specific soil or groundwater sampling, does not identify or evaluate PFAS source areas associated with helicopter operations, fueling, or fire-suppression activities, and fails to assess human health risks.

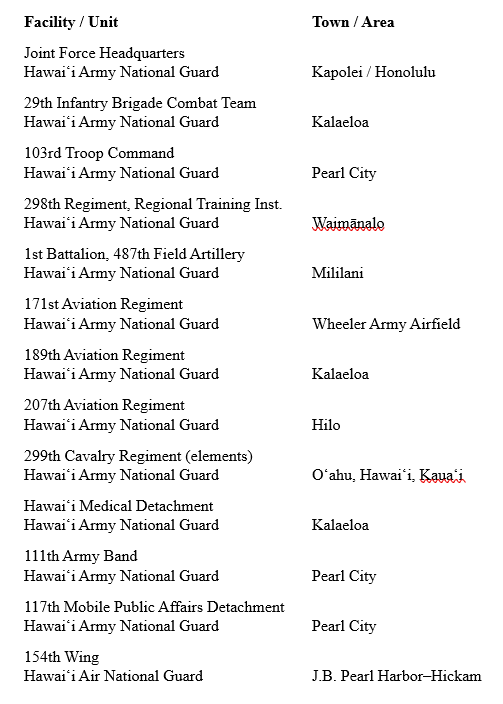

Hawai’i Governor Josh Green and the role of the state

When not federalized, the Governor of Hawaiʻi serves as the Commander in Chief of the National Guard. Day-to-day control of its training and aviation activities rests with the State of Hawaiʻi, not the U.S. Army. Federal dollars fund operations and purchase the helicopters, but this funding does not transfer command authority. The Governor can limit where and how training occurs, impose strict environmental safeguards and require disclosure and monitoring. So far, this has not been the case. Part 4 of this 5-part series will look at Hawaii Army National Guard facilities and their record on PFAS contamination. Following is a list of National Guard facilities in Hawai’i.

A CH-53E Super Stallion

Army helicopter landing zones (HLZs) are permanent ground areas selected to allow rotary-wing aircraft, like the Sikorsky CH-53E Super Stallion to land, unload personnel or equipment, and depart safely during training or operations. Landing Zones are typically established in remote terrain like the Kahuka Training Area

Rotor Wash

Rotor wash is a serious environmental concern. It scours the surface, stripping vegetation, compacting soil, and generating large clouds of toxic dust and debris that can travel downwind.

The CH-53E Super Stallion generates extreme rotor wash, with near-ground wind speeds commonly 80–100 mph and higher during heavy-lift or hover operations, producing sustained, turbulent forces over many thousands of square feet. This wind is powerful enough to strip vegetation, mobilize soil and dust, and scatter gravel and debris, creating erosion and downslope transport pathways. Repeated operations at the same landing zones can therefore physically rework the ground surface, increasing contamination runoff, especially during heavy rain events. They carve a slice into the earth and fill it with a host of contaminants, like surgery with a contaminated blade.

The DOD likes to refer to PFAS as a group of “emerging chemicals” when they knew how toxic these endocrine-disrupting fluorinated compounds were 50 years ago. The Army also refers to the “historic use” of AFFF when the practice is still going on. This is all the Army has to say about PFAS in the entire Final Environmental Impact Statement, and it is not true.

Pyrotechnics at KTA are loaded with PFAS

A 2018 Memorandum for Record from Installation Management Command Pacific documents two training-related fires at Kahuku Training Area, referred to as the X-Strip Fire and the Bravo Gate Fire, which occurred simultaneously. Pyrotechnics, illumination rounds, and simulators were found in the area, linking the fires to military training activity, although the Army lists the exact ignition source as unknown.

The historic concern with pyrotechnics is that they present fire hazards. Today we know it is much worse. According to the Army’s rejected Final Environmental Impact Statement, the Army uses Kahuku for the use of pyrotechnic smokes and artillery simulation devices to simulate engagement with the enemy. Kahuku is prohibited from using aerial pyrotechnics. Only pyrotechnic ground bursts are allowed. The Army says, “pyrotechnics used at KTA involve a small charge, generating a blast effect, and the potential hazard is primarily to the user.”

The PFAS from the flares potentially harm all of us.

Pyrotechnic compositions of Magnesium/Teflon/Viton (MTV) are widely used in military flares and for igniting the solid propellant of a rocket motor. They are comprised of as much as 45% PFAS. The demilitarization of excess, obsolete, or unserviceable flares and other energetic waste currently relies on open burning and open detonation (OB/OD) – a practice that produces an ongoing uncontrolled release of PFAS and other toxic chemicals to the environment. See CSWAB.org.

Sewer System, Wash Rack, Stormwater Management System, Groundwater, and Surface Water Hydrology at the Kahuku Training Area

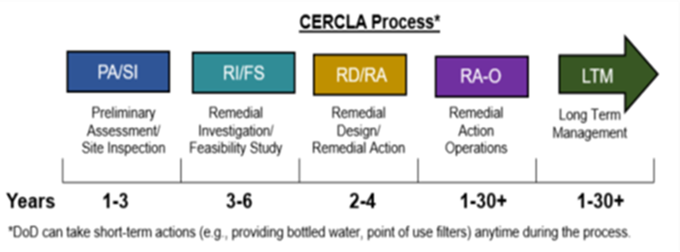

Clean up of contamination in these systems that create carcinogenic pathways to human ingestion is supposed to be regulated by a law called CERCLA.

The Army has made a mockery of the entire CERCLA investigatory and remedial process, a heinous crime perpetrated against humanity around the world. It is a crime that is largely unrecognized by the public. CERCLA, the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, was enacted during the lame-duck session at the end of the Carter administration as Ronald Reagan was on his way into office, promising to gut such nonsense. The bill was rushed and substantially watered down, a compromise that deeply disappointed Senator Edmund S. Muskie of Maine, the law’s principal architect.

It also upset thousands of activists across the country who understood what was at stake. This was 46 years ago.

Senator Edmund S. Muskie, (D) Maine was an environmental hero.

From the outset, the DOD sought to kill the legislation, fully aware that enforceable liability for chronic contamination would expose the military to enormous cleanup obligations. That resistance never disappeared; it merely evolved.

Today, the Army dominates the very regulatory process meant to hold it accountable. It systematically narrows the scope of investigations, minimizes documented contamination, and delays or defers remediation. As it has for decades, the Army chooses to prioritize weapons systems and operational budgets over environmental responsibility, public health, and the communities living with the consequences of military pollution.

PFAS contamination on military installations is addressed under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA).

Under CERCLA, a Preliminary Assessment is a largely paper-based screening that relies on existing records, interviews, and reconnaissance and can either terminate further action or identify “Areas of Potential Interest” to be carried forward. A Site Inspection then involves targeted field work and environmental sampling at those areas to confirm contamination, evaluate potential exposure pathways, and determine whether the site should advance to a full remedial investigation.

The Army has shut down the CERCLA process at the three contaminated bases on O’ahu, while few are paying attention.

This process was meant to be taken more seriously. We ought to be relying on publicly available training records, procurement logs, AFFF inventories, spill reports, fire-response standard operating procedures, state and county disposal records, and soil and groundwater testing! Nope. Everything is fine and dandy. Now run along and mind your own business. Ultimately, the same folks conducting federal investigations into murders in Minneapolis are calling the shots here. Let’s look at what they are telling us about these systems at the Kahuku Training Are. It’s not much.

Sewer System

Wastewater is generated during training at Kahuku and is typically handled on-site through portable toilets and other ad hoc disposal methods that discharge contaminants directly into the earth, rather than being piped offsite or hauled to civilian treatment plants. The Army refuses to disclose details of these cost-saving, waste-handling practices—presumably invoking “national security.” It sounds absurd, but it is entirely consistent with the Department of Defense’s legal posture: when states sue over unchecked PFAS contamination, the federal government routinely asserts sovereign immunity, effectively claiming the authority to poison people and ecosystems in the name of national defense.

Sewer influent includes a mix of residential and industrial sewage. Army shops are known to use and discard volumes of PFAS generated from a host of maintenance activities. At the end of the day much of it goes down the drain. The sewage contains volatile organic compounds, high levels of organic matter, nutrients, pathogens, pharmaceuticals, and other potentially deadly persistent chemicals, along with the PFAS.

The wash rack

In the Preliminary Assessment, the Army mentions the existence of a wash rack only in passing. At Kahuku, the Army claims the wash rack was used merely to wash vehicles “to remove seeds and large clumps of soil that may accumulate on the vehicles prior to leaving the installation.”

That explanation reflects a dystopian level of institutional denial. In reality, wash racks are used to clean military vehicles of fuels, oils, hydraulic fluids, solvents, and firefighting residues—discharging a toxic mixture into the environment that typically includes total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH); jet fuel residues; benzene, toluene, ethylbenzene, and xylenes (BTEX); naphthalene; chlorinated solvents such as trichloroethylene (TCE), perchloroethylene (PCE), 1,1,1-trichloroethane, dichloroethylene, and vinyl chloride—and, of course, PFAS. It is a witch’s brew.

Stormwater Management System

This is all the Army has to say in its Preliminary Assessment for Kahuku:

“Available records do not provide information regarding stormwater management at Kahuku Training Area. However, based on topography, stormwater runoff flows from the mountainous central and southern portions of the Kahuku Training Area towards the northern and eastern installation boundaries.”

Surface waters carry PFAS away.

Responding to the requirements of CERCLA, Air Force and Navy bases on the mainland once produced robust data on PFAS concentrations in stormwater and surface water collected from multiple contaminated locations on base. We don’t know how bad PFAS contamination is in surface water at Kahuku because the Army doesn’t want to tell us.

Hydrogeology

From the Army, “The installation is located within the Northern Koolau Rift Zone, where groundwater discharges to the Pacific Ocean (east and north of KTA); however, the general direction of groundwater flow on the west side of KTA is towards the west.”

“Multiple intermittent and perennial streams transect KTA. The streams flow from the mountainous central and southern portions of KTA towards the northern and eastern installation boundaries. Available records also indicate there is a pond, identified as Onion Pond, located on the south side of KTA. On-installation surface water features are not used as drinking water sources for the installation. Surface water features in the surrounding area include swamps/marshes, lakes/ponds, and streams”

That’s it.

The Army did not test surface water or groundwater for PFAS, the most fundamental indicators of environmental health. This omission was not an oversight. The Army understands these systems intimately. It is not stupid; it is evil.

By design, the Army frames PFAS risk as a drinking-water issue alone, because modern treatment systems can remove much of the contamination before it reaches the tap. What it does not emphasize is that the greatest risks come from the food we eat and the air we breathe. Through decades of releases, the Army has contaminated soils, sediments, crops, wildlife, and dust at bases and surrounding communities around the world, poisoning the food chain while pretending the danger ends at the water meter.

Herbicides

According to the Army’s maligned and rejected Final Environmental Impact Statement, “The Army uses herbicide ground, biological control, aerial (helicopter with a focused nozzle) sprayers, herbicide-painted stumps, weed whacking, and plant removal to control invasive plant species along roads, on training areas, and along fences and utility lines on its training areas on O‘ahu.”

From the Preliminary Assessment: “It was noted during a discussion with a USAEC Pest Management Consultant that the larger group of pesticides are generally not of PFAS concern. Specifically, products containing Sulfluramid (i.e., associated with insecticides) may have contained PFAS and were phased out in 1996. Management Consultant has records of pesticides used and stored at Installation Management Command installations and did not identify Dillingham Military Reservation, Kahuku Training Area, Kahuku Army Support, Kahuku Field Station, Mākua Military Reservation, or Waiawa Army Support Training Area as installations ever containing PFAS-containing pesticides/insecticides.”

(Sulfluramid is entirely made of a kind of PFAS called EtFOSA. It is is a PFOS-precursor. In other words, all of the Sulfuramid sprayed turns to PFOS.)

The Army’s assertion above is not a credible basis to rule out PFAS-containing pesticides at these installations. The quoted statement only says the IMCOM pest management consultant “did not identify” sulfluramid in the records reviewed; it does not establish that sulfluramid was “never” used.

The Army’s pesticide discussion is standardized boilerplate that appears verbatim across numerous PFAS Preliminary Assessment/Site Inspections, including:Tobyhanna Army Depot – South, Fort Buchanan, Fort Hood, Schofield Barracks, Carlisle Barracks, Cornhusker Army Ammunition Plant, Forest Glen Annex, Fort Meade, Fort Bliss, Former Sunflower Army Ammunition Plant, Fort Irwin, Fort Leonard Wood, Letterkenny, and ASF Conroe. This indicates a template-driven screen rather than an installation-specific determination.

Given these numerous Army acknowledgments elsewhere, the claim that none of the six Hawaiʻi installations ‘ever’ had PFAS-containing pesticides is not plausible without full disclosure of the underlying records and search methodology.

Given the continued widespread commercial availability of PFAS-containing pesticides in ant and termite control, and the scale and nature of Army pest-management operations, it is likely that PFAS-containing pesticides were used, and may still be used at Kahuku Training Area and Army installations throughout Hawai’i.

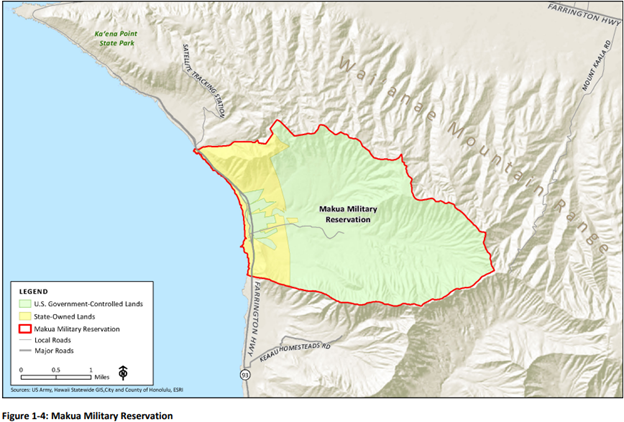

Makua Military Reservation

The Army decided not to renew its lease of the Makua Military Reservation.

The Army has spent a total of $65,000 on PFAS assessment through 2024 and has failed to appropriate additional funding.

The Army’s occupation of Mākua Military Reservation (MMR) stands as one of the most enduring and egregious examples of environmental abuse and colonial disregard in modern U.S. military history. For decades, the Army used Mākua Valley as a live-fire training ground, detonating high-explosive munitions, burning vegetation, and scattering unexploded ordnance across a narrow, steep-walled watershed that drains directly toward nearby communities and the Pacific Ocean.

The Army knew the irreversible damage it was causing.

Mākua has been repeatedly subjected to uncontrolled wildfires ignited by live-fire exercises, including the infamous 2003 fire that burned more than 2,100 acres, terrorizing local communities. Soil erosion, habitat destruction, and the dispersal of the same contaminants, especially the PFAS, mentioned above, have never been comprehensively assessed or cleaned up.

Large portions of the valley remain inaccessible due to unexploded ordnance, which the Army cites as a safety constraint on investigation. If the Army had its way, it would burn the entire 760 acres like they do elsewhere, to extract unexploded ordnance.

Fort Ord after a prescribed burn.

In reality, unexploded ordnance does not make environmental assessment impossible, although it is expensive and time-consuming. The Army routinely conducts UXO clearance at former ranges when compelled to do so. At Mākua, the persistence of unexploded munitions simply reflects a refusal to undertake full remediation.

The Army makes no secret of how central Pōhakuloa is to its Pacific posture. That reality creates a dangerous temptation for state officials: to trade the Army’s promises to clean up Mākua in exchange for continued military use of Pōhakuloa. Such a bargain would be a profound mistake. Cleanup at Mākua—like cleanup at Kahuku and Kawailoa-Poamoho—is not a concession to be negotiated; it is a legal and moral obligation the Army already owes.

Citizens and state leaders must stiffen their resolve. They should reject transactional deals that reward decades of contamination. They must demand the Army’s permanent departure from Pōhakuloa and the full environmental remediation of all lands it has damaged.

Court orders, settlement agreements, and environmental commitments have been treated as bothersome inconveniences rather than obligations to honor.

The Army’s reckless conduct and repeated disregard for Hawaiʻi law have prompted sustained resistance from the courts and state authorities.

Community opposition to the Army’s presence at Mākua is deep and sustained. For Native Hawaiian families, Mākua is a place of cultural, spiritual, and ancestral significance, containing burial sites, sacred features, and traditional agricultural areas.

Protest camps, arrests, lawsuits, and years of organized resistance arose from lived experience: fires, noise, restricted access, environmental degradation, and a bull-headed military institution that refuses to listen.

Across the Pacific region, sustained community opposition to U.S. Army installations has repeatedly been driven by environmental degradation. In places like Okinawa (Torii Station and the Northern Training Area), Camp Fuji in Japan, Camp Humphreys in South Korea, and the U.S. Army Garrison–Kwajalein Atoll in the Marshall Islands, local communities have documented contamination of water and soil, PFAS releases, erosion, habitat destruction, unexploded ordnance, and long-term waste legacies.

These harms are compounded by restricted access to environmental data, and the existence of colonial style Status of Forces Agreements that shield the Army from meaningful local regulation and accountability.

Environmental damage has become the organizing principle of resistance, transforming local grievances into sustained political movements. It is a lesson well known by aggrieved indigenous populations but largely unlearned by European and American antiwar groups.

Activists across the Pacific can learn from Mākua that persistence, documentation, and community-led resistance, combined with litigation and public exposure can make continued military occupation politically and legally untenable.

There are approximately 760 acres of State-owned land within Makua Military Reservation. Multiple helicopter landing zones are located on U.S. Government-owned land. - Preparation Notice, 2023 The 1964 State of Hawaiʻi lease for Mākua Military Reservation (and the related Oʻahu KTA and KLOA leases are fundamentally a surface-land lease, not an independent grant of airspace.

Aerial pyrotechnics have been prohibited at Makua since 2004, but ground pyrotechnics are used, presenting another source of PFAS contamination.

From the 1920s to 2004, Makua was used for small arms and artillery firing, helicopter gunnery practice and maneuvers, tactical live-fire training exercises, and ground training of military troops. After 1970, these operations coincide with heavy use of PFAS in AFFF and a host of products and applications. The Army is not being straight with us regarding PFAS.

The Army likely used PFAS-laced firefighting foams during wildfires

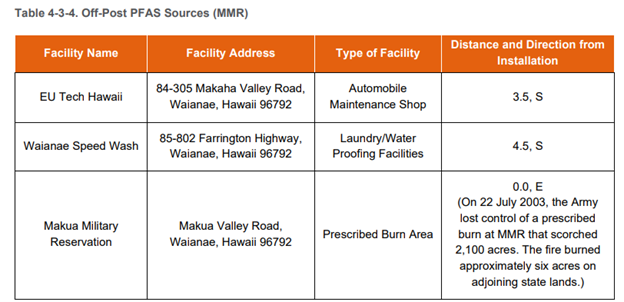

Table 4-3-4 suggests that PFAS-laced firefighting foams were used on base to put out wildfires.

Although Table 4-3-4 is titled “Off-Post PFAS Sources,” the entry for Mākua Military Reservation lists a prescribed burn area at 0.0 miles from the installation, indicating a source located on the base itself. This internal inconsistency suggests that the Army implicitly recognized a PFAS-relevant activity at MMR, associated with a prescribed burn that escaped control in July 2003. While the Army does not disclose whether AFFF or other PFAS-containing firefighting agents were used, the table’s own proximity data supports the conclusion that potential PFAS releases occurred on-post and warranted investigation.

The Army cannot credibly rule out PFAS releases from the 2003 Mākua wildfire while refusing to disclose what firefighting agents were used when a prescribed burn spiraled out of control.

In 2003, PFOS-based AFFF was commonly deployed not only for aircraft fires but also for large, fuel-involved, or ordnance-adjacent fires. Given Mākua’s status as a live-fire training valley with unexploded ordnance and munitions residues, the operational conditions strongly support the likelihood that foam-based suppression methods used to smother hotspots and prevent re-ignition.

While the incident description does not prove that AFFF was deployed, it clearly establishes a credible PFAS release scenario under CERCLA screening standards.

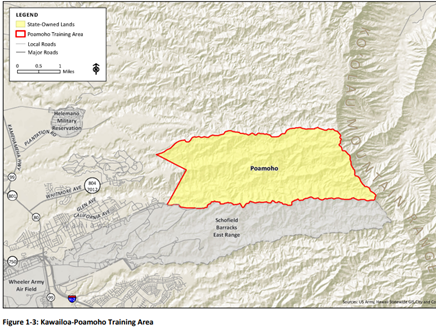

Kawailoa-Poamoho Training Area, (KLOA)

The Kawailoa-Poamoho Training Area shares its preliminary assessment with Schofield Barracks and was also found to be free of PFAS.

The Army will not renew its lease of the Kawailoa-Poamoho Training Area. Figure 1-3, KLOA

- EIS Preparation Notice, 2021.

Kawailoa–Poamoho Training Area is included in the Schofield Barracks report. See the Kawailoa-Poamoho Training Area PA.

The Kawailoa-Poamoho Training Area, (KLOA) borders the Schofield Barracks East Range. KLOA is located on the western slopes of the Ko‘olau Mountain Range. Access to KLOA is very limited due to the lack of improved roads, steep terrain, and dense vegetation.

KLOA is used primarily for Army helicopter aviation training, including repeated low-altitude operations. The Army maintains permanent infrastructure in the area, including multiple helicopter landing zones in the parcel’s northwest corner. KLOA carries the same environmental liabilities documented elsewhere: fuel and lubricant releases, maintenance-related contaminants, erosion, noise impacts, and the potential for PFAS and other persistent pollutants. The Army’s decision to fold KLOA into the broader Schofield reporting structure obscures these risks rather than addressing them, replicating the same pattern of minimization described in the Kahuku Training Area and Makua Military analysis above.

Army says no PFAS here

Document research and personnel interviews conducted by the Army in 2023 provided no indication that historical operations at KLOA included the use, storage, and/or disposal of PFAS-containing materials. Site reconnaissance was not conducted at KLOA and no areas of potential interest were identified. No soil or groundwater samples were collected.

At KLOA, live-fire training ceased in 2004 following a series of wildfires, environmental violations, and sustained community resistance and litigation. Meanwhile, cleanup and restoration remain incomplete. The Army failed to adequately assess environmental and public-health impacts under Hawaiʻi law and the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA).

The Army has identified the No-Action Alternative for Poamoho. “No Action” is effectively an acknowledgment that continued retention of Poamoho cannot be justified under the Army’s own environmental review.

By 2004, opposition to the Army’s occupation of Mākua, Kahuku, and Poamoho was well organized. Activists and attorneys involved in Mākua litigation and Poamoho advocacy understood the leases would expire in 2029, forcing the Army to demonstrate compliance or relinquish the land. Poamoho then entered a prolonged limbo as the lease clock continued to run.

The Army wants to hold on to about 700 acres at the Kahuku Training Area. With its embarrassing track record, the Army ought to be sent packing from all of their leased lands.

This is the 3rd part of a 5-part series.

Part 1 - The Army Is Quietly Walking Away from Oʻahu to Gain Leverage over the Pōhakuloa Training Area

Part 2 - The Army Is Quietly Walking Away from Oʻahu to Gain Leverage over the Pōhakuloa Training Area

This project is supported by financial assistance from the Sierra Club of Hawaii.

Please consider donating to the Sierra Club of Hawai’i. Your donation will continue efforts to achieve Hawaiʻi’s 100% renewable energy goal, defend our oceans and forests, and build a more self-reliant and resilient community that prioritizes justice, enhances natural and cultural resources, and protects public health over corporate profit. Donate Here.