The Army Is Quietly Walking Away from Oʻahu to Gain Leverage over the Pōhakuloa Training Area

An analysis of the state’s rejection of the Army’s Final Environmental Impact Statement, focusing on issues related to toxic contamination

By Pat Elder

January 12, 2026 Part 1 of a 6-part series

Jan. 24, 2024 - Pohakuloa Training Area - Bangalore torpedoes and M18 claymore mines were detonated during a live-explosives training exercise that deposit explosive residues (RDX, HMX, TNT byproducts, metals, etc.) into the fragile environment.

While public attention has focused on the Hawaiʻi Board of Land and Natural Resources’ rejection of the Army’s Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) for the Pōhakuloa Training Area, an equally consequential decision has unfolded largely out of public view. Under its own Record of Decision, the U.S. Army is preparing to vacate thousands of acres of state-leased land on Oʻahu—a move that reshapes the broader negotiations over military land use across the state.

On August 4, 2025, the Army signed its Record of Decision (ROD) for the Environmental Impact Statement governing its Oʻahu training leases. Buried in its conclusions is a stunning outcome: the Army has chosen the No Action Alternative for both Kawailoa-Poamoho Training Area and Mākua Military Reservation, meaning the leases will expire in 2029 and military use will cease.

At Kahuku Training Area, the Army selected Alternative 2, retaining only a portion of the land.

Extracted from the vague language, the decision means the Army will give up all 4,390 acres at Poamoho, all 782 acres at Mākua, and approximately 700 acres at Kahuku. Approximately 5,872 acres of land will return to the state. At Kahuku, the Army will retain 450 of the 1,150 acres it currently leases.

None of this has been reported in local or national media. Instead, spotty coverage has focused almost exclusively on the controversy surrounding Pōhakuloa on Hawaiʻi Island, leaving the false impression that all Army leases remain open for negotiation. They do not.

Under the Army’s final Record of Decision, there is no approved path to renew the Mākua or Poamoho leases. The Army’s obscure language and unwillingness to publicize its departure have hidden its decision to leave. This is part of their strategy.

For decades, the Army’s Oʻahu training areas have been great political and environmental liabilities. Litigation, cultural access disputes, wildfire risk, unexploded ordnance, and unresolved contamination—especially PFAS—have generated sustained public opposition. These sites sit close to population centers and are under constant public scrutiny. From the Army’s perspective, the political cost of holding them now outweighs their training value.

Mākua’s downsizing follows the same strategic thinking. Live-fire training there has been suspended since 2004 following court rulings and legal settlements, yet the site remains a powerful symbol of environmental harm and broken trust with Native Hawaiian communities. Shrinking Mākua allows the Army to claim responsiveness without surrendering control. It is a concession that costs little, feigns cooperation, and avoids confronting the deeper question: why should the Army remain here at all?

Recognizing the destructive impact Mākua has on the island’s land and water, and the reduced importance it has to the Army, the greater Oahu community must demand complete abandonment.

These quiet withdrawals set the stage for the Army’s real priority, the Pōhakuloa Training Area on the Big Island. Unlike the Oʻahu sites, Pōhakuloa is central to the Army’s Indo-Pacific strategy. It has immense operational value. From the Army’s perspective, Pōhakuloa is non-negotiable, while the other leased lands are expendable.

Expect the Army to point to the land it is relinquishing on Oʻahu as evidence of good faith, using those “sacrifices” to strengthen its hand in negotiations over Pōhakuloa.

The Army’s actions do not signal a withdrawal from Hawaiʻi. They represent a calculated consolidation—quietly abandoning politically costly lands on Oʻahu in order to defend long-term control of Pōhakuloa. The state should recognize this strategy for what it is and respond accordingly. Hawaiʻi has more leverage now and it should use it.

The Board of Land and Natural Resources’ 5–2 rejection reflected a determination that the Army’s Final Environmental Impact Statement FEIS did not meet Hawaiʻi law, did not protect public trust lands, and did not justify continued military occupation without enforceable cleanup, accountability, and cultural protections.

The state is under no obligation to weaken its stance as it considers what comes next at Pōhakuloa. The state must strengthen its resolve.

If great injustice prevails, and Hawai’i is forced to accept the continued toxic Army occupation, the new lease should only cover a probationary period of a year or two and it must be armed with enforceable, transparent requirements addressing both legacy and ongoing contamination. These are the issues the Army consistently avoids documenting or committing to remediate under binding standards. They have desecrated the land, and they are intent on continuing to do so.

We are witnessing the 21st century intersection of popular will and imperial overreach.

Pōhakuloa is the cornerstone of the Army’s Indo-Pacific strategy. Unlike the Oʻahu sites, it has fewer immediate neighbors and far greater operational importance. From the Army’s perspective, Pōhakuloa is non-negotiable. As the Army seeks to retain long-term control of Pōhakuloa, it is likely to offer modest, carefully scripted and managed “concessions”, like slightly expanded cultural access, additional monitoring wells they control, and, perhaps, stronger language on fire prevention.

The Army will seek to avoid enforceable reporting and cleanup obligations for a host of chemicals, especially PFAS. They will reject demands that the Hawai’i Department of Health or third parties be granted access to the base to independently conduct environmental testing. The Army will endeavor to control environmental testing protocols and the publication of data.

The Army’s goal is to appear responsive while preserving the core training mission intact, but this is impossible. Preparing for war is dirty business and it creates dirty air, soil, and water that make people sick. It just does.

If the state’s arm is twisted and Hawaii is forced to cry uncle, the state should riddle the lease with enforceable standards and expectations for both legacy and ongoing contamination at Pohakuloa. These are the things the Army doesn’t want to discuss. The Army can be expected to continue its path of obstinance and non-compliance.

If a new lease is thrust upon the state, it must legally compel full transparency by the U.S. Army regarding the exact locations, extent, and concentrations of contamination present on the Island of Hawaiʻi. The lease must demand the construction of a modern wastewater treatment plant with additional filter systems to remove PFAS. The lease must require the Army to fully remediate the substantial environmental damage it has caused, consistent with the most protective international health standards, rather than current weak, federal screening levels. It must further mandate independent third-party monitoring of all identified contaminants, with public reporting, enforceable deadlines, and multi-million-dollar penalties for noncompliance. Critically, the lease must include a clear termination clause requiring the Army to cease operations and vacate the island if contamination limits, monitoring requirements, or remediation obligations are violated.

Anything short of these requirements would amount to continued occupation without accountability, shifting long-term environmental and severe public-health risks onto the people of Hawaiʻi while insulating the Army from responsibility.

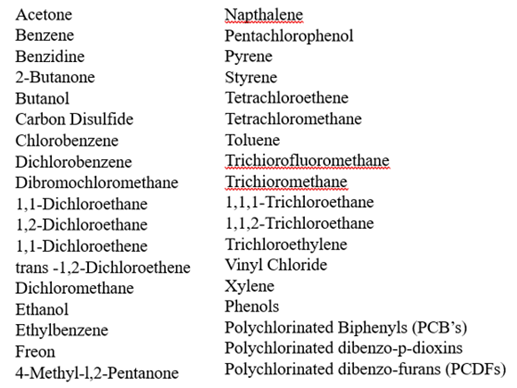

Descriptions of these areas and their accompanying contamination must be included in the new lease. Cleanup protocols and timetables must be included in the lease for each of these areas of contamination, while regular quarterly testing of the contaminants listed below that are known to exist in multiple locations throughout the sprawling facility must be set in motion.

ProPublica’s Freedom of Information Act work with the Department of Defense produced one of the most powerful revelations of military contamination ever assembled. By obtaining and organizing thousands of DoD records, ProPublica exposed the true national scale of toxic legacy pollution, unexploded ordnance, fuels, solvents, and heavy metals—at hundreds of active and former military installations across all 50 states and U.S. territories.

See ProPublica’s 2017 report on Pohakuloa. In its 2017 investigation of the Pōhakuloa Training Area, ProPublica identified 24 contaminated sites on the installation. This report examines each site to determine how—or whether—it is addressed in the Army’s FEIS and to evaluate its likelihood of PFAS contamination.

(1) PU'U PA'A SITE Site ID: PTA-003-R-01

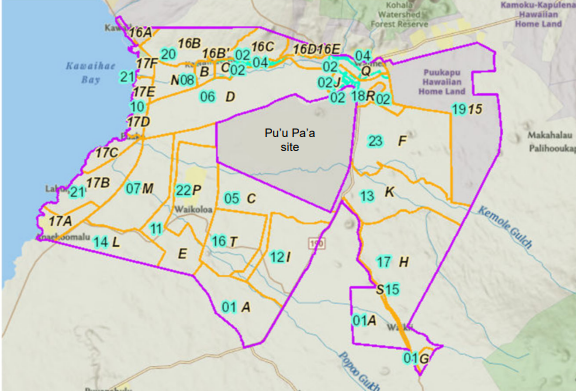

The Pu’u Pa’a Site is shown in the center of the map.

The Pu’u Pa’a Site is comprised of 13,542 acres and was used by the DoD from 1943 to 2000. The property is privately owned and is currently being addressed by Army under the Defense Environmental Restoration Program (DERP), managed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, focused on cleaning up contaminated sites and unexploded ordnance.

The Army says the cleanup will be completed by 2039 and that its estimated cost will be $32 million.

Puʻu Paʻa is part of the former Waikoloa Maneuver Area on the Island of Hawaiʻi. Puʻu Paʻa was returned to private ownership after military use continued through the 1990s. Today, Puʻu Paʻa is privately owned land held by Parker Ranch or Parker Ranch–controlled entities and lies outside the state-leased Pohakuloa Training Area.

The site poses an ongoing public safety risk from accidental detonation and raises environmental concerns related to munitions constituents such as RDX, HMX, TNT, perchlorate, and metals that can persist in soil and dust and potentially migrate.

The Pu’u Pa’a Munitions Response Area is managed separately by the U.S. Army Garrison – Hawaii. This is because the Pu’u Pa’a Local Training Area continued to be used by the Army and the Army National Guard through the 1990s before the property was returned to private ownership, which made the property ineligible for the Formerly Used Defense Sites (FUDS) program. FUDS properties must have been returned before 1987.

Although the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers is involved in implementing investigation and removal work at Puʻu Paʻa, the site is not a FUDS site, and the Army—not the Corps—retains programmatic control, funding authority, and responsibility for the pace of remediation under CERCLA.

The Hawai’i Department of Health Hazard Evaluation and Emergency Response Office is charged with the responsibility to ensure that DoD actions are consistent with the Hawaii Environmental Response Law (HERL), Hawaii Revised Statues (HRS) 128D. See the Explosives Safety Guidance to Help Protect You from Munitions.

Although Puʻu Paʻa is being managed primarily as a munitions response area, the site’s long operational history and routine fire-response needs make PFAS use, especially AFFF use highly plausible. The absence of PFAS discussion in available decision documents should be treated as a data gap, not evidence of absence. The Pu’u Pa’a Waikoloa Maneuver Area is not addressed in the Army’s Final Environmental Impact Statement, (FEIS).

(2) FORMER BAZOOKA RANGE Site ID: PTA-004-R-01 (Described in FEIS).

The Former Bazooka Range measures approximately 60 acres. The site used a rail-mounted moving target for weapons practice. In 2015, the site underwent a surface-only cleanup action that removed 71,300 pounds of material documented as safe, 2,000 pounds of range-related debris, and 81 separate Munitions & Explosives of Concern. The debris was heavily concentrated within an approximately 11-acre central location.

In 2017, surface soil at this site was sampled and analyzed for explosive material and MC metals. Analysis of the soil samples detected concentrations of MC metals above USEPA Region 9 RSLs for Risk-Based Soil Screening for protection of groundwater but below State DOH Tier 1 EALs.

The metals were either below background levels or only above USEPA Region 9 RSLs for protection of groundwater. Due to the arid conditions, lack of streams, and depth of groundwater at the site, which creates a low potential for contaminant mobilization via leaching, as well as the lack of groundwater wells and surface water development in the State-owned land, the metals are not considered COCs that potentially pose an unacceptable risk to site users and warrant further investigation.

Subsurface soils were not evaluated because historical records and land use did not suggest that subsurface soil impacts have occurred.

The Army’s own sampling found munitions-constituent metals above EPA Region 9 screening levels designed specifically to protect groundwater—then dismissed the exceedances by asserting, without supporting measurements, that arid conditions and deep groundwater make leaching unlikely.

The Army’s logic further relies on the absence of wells and streams—confusing lack of monitoring infrastructure with lack of risk—while ignoring heavy storm-driven recharge, preferential pathways in fractured volcanic terrain, and transport via disturbed soils and dust. In plain terms: they exceeded a groundwater-protection screen and chose not to look any deeper.

No land use restrictions have been imposed on the former bazooka range.

Although the former Bazooka Range is being managed primarily as a munitions response area, the site’s long operational history and routine fire-response needs make PFAS use, especially AFFF use very likely. The absence of PFAS discussion in available decision documents should be treated as a data gap, not evidence of absence.

(3) HUMUULA SHEEP STATION-West Site ID: PTA-001-R-01 (Described in FEIS).

Humuʻula Sheep Station–West is a Training and Maneuver Area. Maneuver areas commonly contain chemical residues from pyrotechnics, illumination rounds, simulators, flares, and propellants used during training. These materials can introduce perchlorate, polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs) such as naphthalene, and munitions-constituent metals including copper, lead, antimony, and barium into surface soils. Repeated soil disturbance and dry conditions increase the likelihood that these contaminants persist, migrate as dust or runoff, and pose long-term exposure risks that are not captured by limited surface-soil screening alone.

Pyrotechnics involve heavy uses of PFAS. See: CSWAB.

Humuʻula Sheep Station–West (Site ID PTA-001-R-01) has been formally designated by the Army as a CERCLA site.

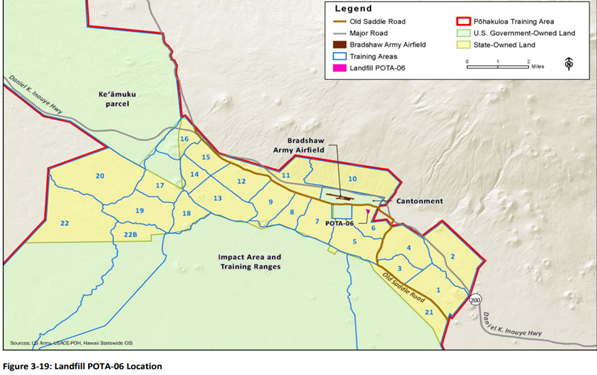

(4) LANDFILL 2 Site ID: POTA-06 (Described in FEIS).

Landfill 2 POTA – 06 is located adjacent to Bradshaw Army Airfield. The two combine as an expected PFAS hotspot.

The former POTA-06 landfill was opened in 1979 and closed in October 1993. LANDFILL 2 is a recognized CERCLA waste site within Pōhakuloa Training Area. As a buried landfill associated with decades of military operations, it represents a presumptive source of heavy concentration of PFAS, metals, petroleum hydrocarbons, solvents, and other contaminants that can persist and migrate through soil and groundwater. Any conclusion that this site does not warrant further investigation must be supported by site-specific subsurface data, not generalized assumptions about aridity or current land use.

According to the FEIS, “To remedy landfill POTA-06, which is on the State-owned land in TA 6, the Army at one time monitored methane emissions from the landfill. After eight sampling events indicated that no methane was being produced from the landfill, the DOH approved the elimination of methane monitoring in May 2012.”

The assertion that Landfill POTA-06 produced no methane after eight sampling events—and therefore warranted termination of methane monitoring—lacks credibility, as methane generation is a well-established and often intermittent byproduct of landfills containing organic material, with emissions that can vary spatially and temporally and are not reliably ruled out by a limited number of discrete sampling events.

(5) FORMER FFTA PIT Site ID: POTA-01

The Former Firefighter Training Area Pit (POTA-01) at Pōhakuloa Training Area is a documented Fire/Crash Training Area where fuels were historically burned for emergency response training. Such sites are associated with massive PFAS contamination from the use of aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF) during firefighting exercises.

It is impossible to match this area, POTA-01 with the fire training areas described in the current PFAS preliminary assessment / site inspection. The Army changes its designations of these toxic areas, confusing the public.

The Former FFTA Pit is not addressed in the FEIS.

(6) FORMER STG AREA BEHIND BLDG T-31 Site ID: POTA-02

The Former Small-Arms Training and Gunnery Area behind Building T-31 (POTA-02) at Pōhakuloa Training Area is a legacy small-arms training area where weapons firing and related activities historically occurred adjacent to support facilities. Such areas commonly contain munitions debris and metals (including lead, copper, and antimony) in surface soils, with risks heightened by erosion, dust generation, and disturbance. Like the other live fire sites, they are associated with the use of firefighting foams containing PFAS.

This site is left out of the FEIS.

(7) ARTILLARY FIRING AREA POWDER BURN Site ID: POTA-04

The Artillery Firing Area – Powder Burn at Pōhakuloa Training Area is a legacy training location where excess artillery propellant (powder charges) was intentionally burned or detonated during live-fire operations. These activities can leave residual energetic compounds, perchlorate, and metals in soil, along with buried or surface munitions debris, posing long-term environmental and safety concerns.

The current burn pan is within PTA immediately south of TA 13 along the southern boundary of the State owned land (i.e., adjacent to but not on State-owned land). The burn pan is a low-lying rectangular-shaped area located on a graded ‘a‘a lava flow. The burn pan has been in operation since the late 1990s/early 2000s. Military units dispose of excess propellant bags/increments incidental to artillery firing training through on-site powder burns at the completion of training.

Although the Army does not associate the burn pan as a PFAS source, aqueous AFFF commonly accompanied live-fire and artillery training activities at Army installations nationwide.

This site is left out of the FEIS.

(8) IMPACT AREA Site ID: POTA-07

Decades of live-fire training in the approximately 51,000-acre federally owned impact area have left a complex toxic legacy that includes explosive compounds, heavy metals, and perchlorate from propellants and pyrotechnics, as well as petroleum hydrocarbons from fuels and lubricants. It’s not good.

The Hawaiʻi Board of Land and Natural Resource determined that impacts originating in this area, including wildfire emissions, unexploded ordnance (UXO), and resulting contamination, directly affect state trust lands and shared ecosystems.

The Army’s FEIS failed to analyze the impact area.

(9) Petroleum, Oil, Lubricants (POL) STORAGE AREA Site ID: POTA-09

The POL Storage Area is associated with historical storage and handling of fuels, oils, and lubricants. Such sites are well-documented sources of petroleum hydrocarbons, BTEX compounds, (Benzene, Toluene, Ethylbenzene, Xylene), PAHs such as naphthalene, metals, and often chlorinated solvents used in fuel-system maintenance. Any conclusion that this site does not warrant further investigation must be supported by subsurface soil and groundwater data, not generalized assumptions about site conditions or current land us. AFFF has always been an integral part of these programs on Army facilities.

This site is left out of the FEIS.

(10) UNDERGROUND STORAGE TANKS SITES (7) Site ID: POTA-10 (Described in FEIS).

The Underground Storage Tanks (UST) Sites (7) (POTA-10) at Pōhakuloa Training Area consist of multiple locations where fuel and petroleum products were historically stored in buried tanks to support training operations. Leaks and releases from these tanks are commonly associated with petroleum hydrocarbons TPH, BTEX contamination in soil and potentially groundwater. Although the tanks have been removed or closed, these sites represent legacy contamination on state-owned land leased to the Army.

PFAS contamination is associated with underground storage tanks, not necessarily through fuel releases, but through the widespread historical use of PFAS-containing materials in seals, gaskets, O-rings, hoses, coatings, lubricants, and other UST system components that degrade and leach into surrounding soils over time.

(11) MAINTENANCE AREA (WSC #5) Site ID: POTA-11

The Maintenance Area (WSC #5) at Pōhakuloa Training Area is a legacy support area where vehicle and equipment maintenance historically occurred, activities commonly associated with releases of petroleum hydrocarbons, solvents, lubricants, metals, and degreasers like trichloroethylene (TCE) into surrounding soils. Such areas can pose long-term environmental risks through soil contamination and potential migration to groundwater, particularly where historic practices lacked modern containment. Located on state-owned land leased to the Army, the site is addressed under the Army’s CERCLA-based environmental restoration program, contributing to broader concerns about cumulative contamination and the adequacy of cleanup at PTA.

Maintenance areas on Army installations are associated with the storage and use of AFFF. This area is not addressed in the FEIS.

(12) AMMUNITION STG MAGAZINES (8) Site ID: POTA-12

The Ammunition Storage Magazines (8) (WSC #8) at Pōhakuloa Training Area comprise multiple facilities used to store military munitions and explosives in support of training operations. While not firing ranges, such areas are commonly associated with explosive residues, propellants, perchlorate, and metals from handling, storage, and occasional spills or deterioration of munitions, as well as buried debris from past operations. Situated on state-owned land leased to the Army, these sites are addressed within the Army’s CERCLA-based environmental restoration and munitions management framework, underscoring ongoing concerns about legacy contamination, investigation rigor, and long-term stewardship at PTA.

Like the other sites that involve handling of munitions and explosives, these areas are associated with AFFF storage and usage. These sites are not addressed in the Army’s FEIS.

(13) FOAM STORAGE SHED Site ID: POTA-13

The Foam Storage Shed (WSC #9) at Pōhakuloa Training Area is a legacy support site used to store firefighting foams, historically including aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF). Spills, leaks, or equipment rinsing at such facilities are a well-documented source of PFAS contamination in soil and potentially groundwater, even where active use has ceased. Located on state-owned land leased to the Army, the site is addressed under the Army’s CERCLA environmental restoration framework, making it a focal point for concerns about PFAS investigation, cleanup adequacy, and long-term monitoring at PTA.

There is no mention of this obvious PFAS-related site in the FEIS.

(14) UNDERGROUND STORAGE TANKS SITE Site ID: POTA-14

The Underground Storage Tanks Site (WSC #10) at Pōhakuloa Training Area is a legacy fuel-storage location where petroleum products were historically stored in buried tanks to support military operations. Releases from aging or improperly closed tanks are commonly associated with petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH) and BTEX compounds, with the potential to contaminate surrounding soils and, under certain conditions, groundwater. Situated on state-owned land leased to the Army, this site is managed under the Army’s CERCLA-based environmental restoration program, contributing to ongoing concerns about legacy fuel contamination and long-term stewardship at PTA.

These sites are not addressed in the Army’s FEIS.

(15) FORMER TRANSFORMER STG AREA Site ID: POTA-15 (Described in FEIS).

The Former Transformer Storage Area (WSC #13) at Pōhakuloa Training Area is a legacy site where electrical transformers were historically stored and handled, activities commonly associated with releases of polychlorinated biphenyls (PCBs) as well as petroleum oils and metals from leaks or spills. Even small releases can result in persistent soil contamination with long-term human and ecological risks. Located on state-owned land leased to the Army, the site is addressed under the Army’s CERCLA-based environmental restoration program, raising ongoing concerns about investigation thoroughness, cleanup standards, and long-term monitoring at PTA.

The Army says in the FEIS that discharges from pad-mounted transformers are small quantities, resulting from slow corrosion of transformer components due to weather exposure. Slow discharges tend to be absorbed rapidly into the soil surrounding the transformer pad and have minimal potential of entering waterways or storm drainage systems.

PFAS is associated with former transformer storage areas due to the historical use of AFFF for fire suppression, PFAS-containing electrical insulation, fluorinated seals and gaskets, PTFE-based lubricants, and PFAS-treated spill response materials, all of which can degrade and leach into surrounding soils over time.

(16) 43 SEPTIC TANKS/12 LEACH WELLS Site ID: POTA-16 (Described in FEIS).

The 43 Septic Tanks / 12 Leach Wells at Pōhakuloa Training Area represent a widespread legacy of a dangerous wastewater disposal system used to support housing, training, and support facilities across the installation. Such systems are commonly associated with releases of PFAS, nutrients, pathogens, petroleum residues, solvents, metals, and emerging contaminants, with leach wells posing a direct pathway to groundwater in Hawaiʻi’s highly permeable volcanic soils. These sites are located on state-owned land leased to the Army.

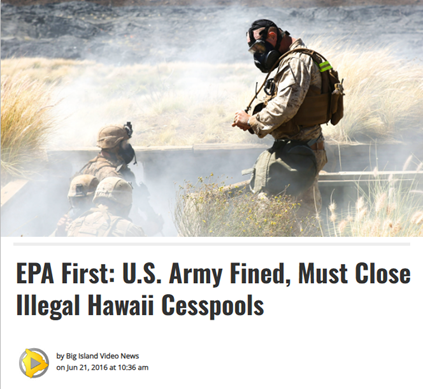

The 2025 FEIS states that the Army continues to rely on cesspools and that they are regulated by the Hawaii Department of Health. The law calls for their abolition by 2050. The Army previously operated "large-capacity cesspools" at PTA, which were banned by the EPA in 2005. The Army continued using them until a 2016 enforcement action forced their closure.

"Small-capacity" cesspools at a massive military installation like PTA should be held to higher standards than residential systems due to the potential for industrial or chemical runoff, including PFAS contaminants. It is good to see kmovement in the legislature on this matter.

(17) UNDERGROUND STORAGE TANKS BLDG 186 Site ID: POTA-17

The Underground Storage Tanks at Building 186 at Pōhakuloa Training Area are a legacy fuel-storage site associated with historic operations and facility support activities. Leaks or releases from these tanks are commonly linked to petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH) and BTEX compounds, which can persist in soil and pose a risk to groundwater in Hawaiʻi’s permeable volcanic geology. Situated on state-owned land leased to the Army, the site is addressed under the Army’s CERCLA-based environmental restoration program, contributing to broader concerns about legacy fuel contamination, investigation adequacy, and long-term stewardship at PTA.

The tanks are associated with PFAS, while these sites are not addressed in the Army’s FEIS.

(18) VEHICLE REFUELING AREA Site ID: POTA-18 (Described in FEIS).

The Vehicle Refueling Area at Pōhakuloa Training Area is a legacy operational site where fuels were routinely transferred and stored to support military vehicles and equipment. Such areas are commonly associated with petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH), BTEX compounds, and fuel additives in soil from chronic spills and leaks, with the potential to migrate toward groundwater in Hawaiʻi’s highly permeable volcanic terrain. Located on state-owned land leased to the Army, the site is managed under the Army’s CERCLA-based environmental restoration program, underscoring ongoing concerns about legacy fuel contamination, cleanup adequacy, and long-term monitoring at PTA.

Vehicle refueling areas are credible PFAS source zones because PFAS were historically used not only in firefighting foams, but throughout fuel-handling, safety, and maintenance operations. PFAS-containing materials are embedded in fluoropolymer-lined hoses, gaskets, O-rings, valve seals, and flexible connectors designed for chemical resistance.

(19) EQUIPMENT STORAGE AREA Site ID: POTA-19

The Equipment Storage Area at Pōhakuloa Training Area is a legacy support site used to store military vehicles, machinery, and materials in support of training operations. Such areas are commonly associated with PFAS, petroleum hydrocarbons, lubricants, solvents, metals, and battery-related contaminants from leaks, spills, and long-term outdoor storage on unpaved surfaces. Situated on state-owned land leased to the Army, the site is addressed under the Army’s CERCLA-based environmental restoration program, contributing to ongoing concerns about cumulative contamination and the adequacy of investigation and long-term stewardship at PTA.

This site is not addressed in the FEIS.

(20) ABANDONED LANDFILL 1 Site ID: POTA-03

The Abandoned Landfill 1 at Pōhakuloa Training Area is a legacy disposal site where solid waste from military operations was historically buried or dumped without modern liners or leachate controls. Such landfills are commonly associated with mixed contaminants, including petroleum hydrocarbons, solvents, metals, unexploded debris, and PFAS-containing materials, with leachate posing a long-term risk to soil and groundwater in Hawaiʻi’s highly permeable volcanic geology. Located on state-owned land leased to the Army, the site is managed under the Army’s CERCLA-based environmental restoration program, underscoring persistent concerns about uncharacterized waste, inadequate cleanup, and long-term environmental stewardship at PTA.

We don’t know when this landfill was in service. Because Abandoned Landfill 1 is described as a “legacy disposal site,” this likely means it was associated with solid waste disposal practices that pre-date modern environmental controls. On Army installations, such landfills were commonly established and used from the 1950s through the 1970s or early 1980s. Solid waste containing PFAS began to be disposed of in landfills in the 1960's while AFFF was introduced in the early 1970's.

This important site is not addressed in the Army’s FEIS.

(21) HUMUULA SHEEP STATION-EAST HUMUULA SHEEP STATION-EAST Site ID: PTA-001-R-02 (Described in FEIS).

Humuʻula Sheep Station–East is a Training and Maneuver Area within the Army’s Pōhakuloa Training Area on Hawaiʻi Island that has been used for decades for ground troop and vehicle maneuvers rather than concentrated live-fire training. Although not primarily a firing range, repeated military use can leave munitions debris, petroleum residues, metals, and compacted or eroded soils, with dust generation and runoff posing ongoing environmental concerns. The area lies on state-owned land leased to the Army and is managed as part of PTA’s broader training footprint, making it relevant to cumulative-impact, stewardship, and lease-renewal debates surrounding the installation.

While not expected to be as heavily impacted by PFAS as the Humuʻula Sheep Station–West, the military activities here are likely associated with AFFF usage.

(22) BRADSHAW FIELD STORAGE AREA Site ID: POTA-08

The Bradshaw Field Storage Area (WSC #2) at Pōhakuloa Training Area is a legacy support site used for the storage of military equipment, materials, and supplies associated with training operations. Activities at such storage areas are commonly linked to PFAS, petroleum hydrocarbons, lubricants, solvents, metals, and battery-related contaminants from leaks, spills, and long-term outdoor storage. Located on state-owned land leased to the Army, the site is addressed under the Army’s CERCLA-based environmental restoration program, contributing to ongoing concerns about legacy contamination, investigation adequacy, and long-term environmental stewardship at PTA.

This site is not mentioned in the Army’s FEIS.

(23) KULANI BURN PILE Site ID: PTA-002-R-02

The Kulani Burn Pile at Pōhakuloa Training Area is a legacy waste-disposal site where debris and surplus materials were historically open-burned, a practice commonly associated with residual ash, metals, petroleum byproducts, and partially combusted compounds in surface soils. Open burning can leave persistent contamination and mobilize pollutants through windblown dust and runoff, particularly in PTA’s exposed, high-elevation environment. Burn piles are historically associated with high concentrations of PFAS. The important site is located on state-owned land leased to the Army and it does not appear in the Army’s FEIS.

(24) KULANI BOYS' HOME KULANI BOYS' HOME Site ID: PTA-002-R-01 Kulani Boys’ Home is a historic former juvenile correctional facility located adjacent to the Pōhakuloa Training Area that has been impacted by nearby military training and disposal activities, including unexploded munitions, munitions debris, and contamination associated with burning and live-fire operations in the surrounding Kulani area. The proximity of the former residential facility to active and legacy military sites underscores long-standing public safety and environmental concerns, particularly regarding UXO hazards, and soil contamination.

Live fire operations are associated with AFFF use. This site does not appear in the Army’s FEIS.

Other sites identified in the FEIS

The FEIS identified three former ranges: a Former Bazooka Range, Former Tank Gunnery Range, and Potential Former Burn Pan. No land use restrictions have been imposed on any of these sites. The Army considers these ranges to be operational, although live fire is not currently conducted.

The Army says these locations have the potential to contain Munitions and Explosives of Concern (MEC). This term is used to describe military munitions that pose an explosive safety hazard due to their physical condition, location, or lack of accountability. MEC include: Unexploded Ordnance (UXO), Discarded Military Munitions (DMM), and Munitions Debris with Explosive Potential.

The Former Bazooka Range, including the High Mortar Concentration Area, contains 60 acres. In 2015, the site underwent a surface-only cleanup action that removed 71,300 pounds of material documented as safe, 2,000 pounds of range-related debris, and 81 MEC items. Subsurface military munitions at this site have not been addressed.

In 2017, surface soil at this site was sampled and analyzed for explosive material and MC metals. Analysis of the soil samples detected concentrations of MC metals above USEPA Region 9 standards for protection of groundwater.

The Army concludes, “ Due to the arid conditions, lack of streams, and depth of groundwater at the site, which creates a low potential for contaminant mobilization via leaching, as well as the lack of groundwater wells and surface water development in the State-owned land, the metals are not considered contaminants of concern that potentially pose an unacceptable risk to site users and warrant further investigation.

The Army’s determination of no further action at the Former Bazooka Range is not supported by the facts or by sound environmental science. Although a surface-only cleanup removed debris and visible munitions, subsurface military munitions—the primary long-term source of contamination—remain unaddressed. Subsequent soil sampling detected munitions-related metals at concentrations exceeding USEPA Region 9 standards for protection of groundwater, yet these exceedances were dismissed based on assumptions about arid conditions, deep groundwater, and the absence of monitoring wells.

It’s the same argument again.. In Hawaiʻi’s fractured volcanic terrain, however, episodic heavy rainfall, preferential flow paths, and perched water zones can mobilize contaminants despite low average rainfall, and the lack of wells reflects a lack of monitoring, not a lack of risk.

The no-action finding fails to account for the cumulative and enduring environmental harm associated with unresolved subsurface munitions and metal contamination at the site. And, of course, firefighting foams and PFAS in various components are also expected to be part of the scene.

The Former Tank Gunnery Range

This site was operational as a tank gunnery range in the 1950s and possibly up until the early 1960s

There are no records of a cleanup action being performed at this site. In 2017, surface soil was sampled and analyzed for explosive material and MC metals. The soil samples contained no concentrations of these contaminants above USEPA Region 9 RSLs.

The Army says subsurface soils were not evaluated because historical records and land use did not suggest that subsurface soil impacts have occurred.

The assertion that subsurface soil impacts are unlikely at a former tank gunnery range because historical records and land use do not suggest such impacts is difficult to support. Tank gunnery operations in the 1950s involved repeated live-fire exercises using high-energy munitions that routinely resulted in buried fragments, ricochets, and unexploded ordnance.

A tank gunnery range is reasonably expected to contain a broad suite of contaminants tied to decades of live-fire and support activities. These include munitions and explosives of concern, energetic compounds such as TNT, RDX, HMX, DNTs, nitroglycerin, and nitrocellulose from high-explosive and propellant residues.

These chemicals are readily absorbed through ingestion of contaminated water, inhalation of dust or vapors, and dermal contact, and several are known or suspected carcinogens.

Munitions-constituent metals including lead, copper, antimony, zinc, barium, chromium, nickel, and tungsten are shed from projectiles, fragments, and primers.

The tank gunnery range spread perchlorate from propellants, igniters, tracers, and pyrotechnics. Polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons (PAHs), notably naphthalene, are produced from detonations.

Where armor-piercing testing occurred or was possible, depleted uranium (DU) must also be examined, although the Army doesn’t mention it in their Environmental Impact Statement.

Depleted Uranium

A Davy Crockett Weapon System at the

Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland, 1961

See Radioactive Materials, p 3--17 in the Army’s FEIS.

The Army’s FEIS acknowledges that depleted uranium (DU) was used at the Pōhakuloa Training Area (PTA) during training involving the Davy Crockett Weapon System between 1962 and 1968. According to the FEIS, DU was present in the M101 20-millimeter spotting rounds fired to aim the weapon prior to launching high-explosive practice projectiles. Each spotting round contained approximately 0.5 pound of a depleted uranium–molybdenum alloy. The Army reports that no more than 400 rounds were fired at PTA, corresponding to a total potential DU deposition on the order of 200 pounds. Depleted uranium is chemically toxic and radiologically hazardous, with a half-life measured in billions of years.

The Army states that these rounds were fired at four ranges within PTA. Of these, three ranges are entirely on U.S. Government-owned land, while one range—Range 13 on Training Area 9—is partially on State-owned land.

The Army distinguishes between state-owned and federally owned land while this has no environmental relevance. Radiation does not respect jurisdictional lines. Wind, stormwater runoff, soil disturbance, wildfire, and human activity do not stop at survey boundaries.

The Army’s reliance on ten surface soil samples to dismiss the presence of DU is also alarming. The absence of DU in a small number of surface samples does not demonstrate absence of contamination. No systematic subsurface DU investigation has been conducted, despite the acknowledged firing of hundreds of DU projectiles.

Former Burn Pan

“Approximately 0.4 acre of the site was used as a burn pan prior to the mid-1990s. A burn pan is an area where excess military munition propellant is ignited for disposal treatment.

The Army claims they do not know materials were disposed of at this site. In 2017, surface soil was sampled and analyzed for polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbons, explosive material, and MC metals. The soil samples contained concentrations of naphthalene (a polycyclic aromatic hydrocarbon) and copper (a metal) above the USEPA Region 9 RSLs but below State DOH Tier 1 EALs.

The Army does not share the results of this sampling.

“Additionally, copper is not a concern because the pathway for leaching to groundwater is incomplete due to site conditions and the lack of groundwater wells and surface water development in the State-owned land.”

Seriously? The assertion that copper is “not a concern” because the leaching pathway to groundwater is incomplete due to site conditions and the absence of groundwater wells or surface water development reflects a fundamental misunderstanding of contaminant transport and risk assessment. The lack of groundwater wells does not interrupt a pathway; it merely prevents detection.

Declaring copper harmless because it has not been measured in groundwater substitutes administrative convenience for environmental protection and improperly shifts risk to future generations.

Army burn pans, or pits, were routinely used for firefighting training and, following the adoption of AFFF in the early 1970s, regularly involved repeated discharges of PFAS-containing foam directly onto unlined ground, making these sites among the most significant PFAS source areas on military installations. The Army left this most significant out of the FEIS narrative.

No mention of trichloroethylene (TCE)

A review of all publicly available Army environmental documents for Pōhakuloa Training Area, including the Final Environmental Impact Statement, shows no mention of trichloroethylene (TCE).

Storage areas and landfills are well-documented historical sources of chlorinated solvents, like TCE. The absence of any publicly available analytical data accompanying the FEIS raises serious concerns that relevant contaminants were not evaluated.

The Hawaiʻi Board of Land and Natural Resources’ (BLNR) rejection of the U.S. Army’s Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS)

The FEIS consists of four volumes containing 3,598 pages:

Final EIS – Vol. I

Final EIS – Vol. 2

Final EIS – Vol. 3

Final EIS – Supporting Documents

The Board of Land and Natural Resources’ (BLNR) raised serious and well-founded concerns regarding a broad range of Army activities—including the desecration of ancestral and culturally significant lands, the ignition of recurrent wildfires, and the perpetuation of economic and environmental inequities. Those issues, though grave, are not the primary subject of this analysis. The discussion that follows is limited to the Board’s findings as they relate to contamination, environmental health, and the Army’s failure to adequately characterize and disclose toxic risks associated with continued military use of public trust lands.

The Pōhakuloa Training Area (PTA) covers approximately 132,000 acres on Hawaiʻi Island, including a vast federally owned live-fire impact area and approximately 23,000 acres of State of Hawaiʻi land leased to the U.S. Army. The lease expires on August 16, 2029. The Army proposes to retain up to 22,750 acres of State-owned land in support of continued military training.

On May 9, 2025, the Hawaiʻi Board of Land and Natural Resources (BLNR) voted 5–2 to reject the Army’s Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) for the proposed retention of State-owned lands at the Pōhakuloa Training Area (PTA). The Board determined that the FEIS failed to satisfy the disclosure and analytical requirements of the Hawaiʻi Environmental Policy Act (HEPA), Chapter 343, Hawaii Revised Statutes

The Army’s desecration of lands on the Big Island represents a dangerous constitutional clash between federal overreach and the state of Hawaiʻi’s sovereign authority to protect its lands, waters, and people.

In light of the deficiencies described in the preceding section of this report, the Hawaiʻi Board of Land and Natural Resources had no reasonable alternative but to reject the Army’s Final Environmental Impact Statement. The Board’s decision was grounded in the Army’s failure to satisfy the legal and procedural requirements of Hawaiʻi Revised Statutes Chapter 343, particularly its obligation to fully disclose and rigorously evaluate environmental impacts. The BLNR concluded that the FEIS did not adequately analyze the consequences of continued military use of state-leased lands or the federally owned impact area and instead relied on outdated, incomplete, or missing data.

BLNR expressed alarm over the inadequate analysis of impacts to biological resources, the absence of clear information regarding cleanup obligations upon the return of the land, and unresolved conflicts with Conservation District land-use purposes. The people of Hawaiʻi are fortunate to be served by a board that acted with honesty, courage, and integrity in issuing its historic rejection of the Army’s pseudo-scientific Final Environmental Impact Statement.

After hearing hours of passionate testimony from community members, the Board of Land and Natural Resources (BLNR) voted not to accept the United States Army’s Final Environmental Impact Statement (FEIS) for the proposed retention of state-owned lands at Pōhakuloa Training Area (PTA) on Hawaiʻi Island. May 9, 2025 - BLNR

A primary deficiency identified by BLNR is the Army’s failure to evaluate environmental desecration within the federally owned impact area. Although the Army limited its analysis to lands leased from the State, BLNR concluded that this approach improperly constrained the FEIS’s area of influence. Under HEPA, an environmental review must consider all reasonably foreseeable impacts of the proposed action, including those occurring on adjacent or connected lands when activities function as a single operational unit.

Decades of live-fire training in the approximately 51,000-acre federally owned impact area have left a complex toxic legacy that includes explosive compounds such as TNT, RDX, and HMX. Heavy metals including lead, copper, antimony, tungsten, and depleted uranium residues are prevalent. Perchlorate from propellants and pyrotechnics, as well as petroleum hydrocarbons from fuels and lubricants abound. These chemicals are associated with munitions, flares, and firefighting activities. We will examine PFAS in a later section.

Many of these contaminants persist in soil and sediments, can be mobilized by wind, wildfire, and intense rainfall, and pose long-term risks to groundwater, ecosystems, and human health.

Firing a single 5.56 × 45 mm NATO round is an environmental catastrophe in itself. The bullet contains a copper jacket, steel penetrator, and a lead core, along with propellant residues of nitrocellulose-based powders. Together, they contribute to neurological, cardiovascular, and developmental health effects with chronic exposure. One bullet..

When fired in large quantities, these materials fragment and accumulate in soils, contributing to lead, copper, antimony, and other metal contamination at firing points and downrange impact areas.

BLNR determined that impacts originating in this area, including wildfire emissions, unexploded ordnance (UXO), and resulting contamination, directly affect state trust lands and shared ecosystems. By excluding the impact area from analysis, the FEIS failed to disclose cumulative and indirect effects that are inseparable from continued military use of the leased lands. BLNR concluded that such segmentation undermines the purpose of environmental review and prevents informed decision-making.

Where is the Army’s data?

It is conspicuously absent.

Volume III of the FEIS contains the entire Preliminary Assessment and Site Inspection of PFAS for Pohakuloa Training Area and Kilauea Military Reservation, Hawaii, 2023. We will examine this in detail in a subsequent section.

A review of the Schofield Barracks Federal Facilities Agreement (FFA), executed in 1992, documents the routine use, release, and monitoring of several dozen toxic compounds at that installation, including chlorinated solvents, fuels, metals, PCBs, explosives-related compounds, and other hazardous substances. Given the shared command structure, overlapping logistics, and decades of similar training and maintenance activities, most—if not all—of these compounds can reasonably be expected to have been used, released, or disposed of at the Pōhakuloa Training Area as well.

Yet, the Army’s Final Environmental Impact Statement references only a small subset of these contaminants, and then, only in passing, without presenting corresponding sampling results, baseline concentrations, or trend data. The absence of comprehensive contaminant data prevents meaningful assessment of environmental conditions at PTA and undermines the FEIS’s claim to disclose the full scope of environmental impacts, as required under Hawaiʻi Environmental Policy Act. The Army’s response is preposterous.

At Schofield Barracks, the examination of dozens of chemical compounds occurred as part of the initial CERCLA (Superfund) process that preceded the Federal Facilities Agreement (FFA). The Pōhakuloa Training Area has never been designated a Superfund site, although it much larger, more intensively used for live fire, and more heavily contaminated than Schofield Barracks. Let’s briefly look at the toxins examined at Schofield Barracks the Army ignored at Pōhakuloa.

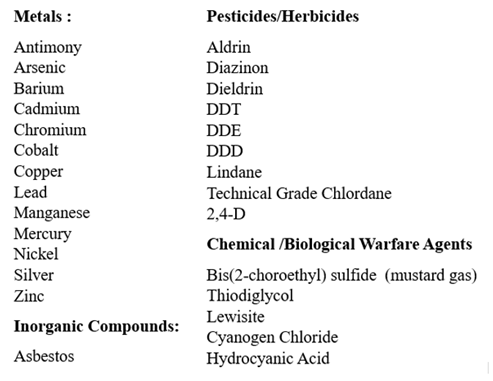

Organic Compounds in the Schofield Barracks FFA:

The Army’s FEIS on PTA provides no meaningful analysis of any of the compounds above. A handful of these toxins are mentioned in passing by the Army. See the notes below, along with corresponding pages from the FEIS Vol I.

One member of the BLNR approved the Army’s FEIS while another abstained.

Asbestos – the Army’s FEIS rules out the presence of Asbestos on state-leased lands. FEIS Vol I 3-112

PCB’s - Based on a Polychlorinated Biphenyl (PCB) survey conducted in the early 1990s, no transformers or other equipment containing PCBs were located on the State-owned land FEIS Vol I 3-112

Antimony, Lead, and Zirconium - Soil samples collected from the BAX Target V-10 area contained concentrations of Contaminants of Concern (antimony, lead, and zirconium) that potentially pose unacceptable risks to site users. FEIS Vol I 3-111 However, the Army provides no data, no mitigation strategies, and concludes, “The arid conditions, lack of perennial or intermittent streams, depth to groundwater, and the Army Training Land Retention at Pōhakuloa Training Area Final Environmental Impact Statement’s relatively conservative models used to establish the screening levels limit the groundwater pathway.”

Arsenic is mentioned once. “Release mechanisms for potential contamination from training activities may include off-range flow of surface water, erosion, and deposition (via surface water) of soil, and infiltration into groundwater, if Standard Operating Procedures and Best Management Practices are not followed. The Phase II Environmental Condition of the Property (ECOP) surface soil sampling concluded that the contaminants detected in soils [i.e., antimony, arsenic, cobalt, copper, iron, 1-methylnaphthalene, lead, manganese, naphthalene, selenium, silver, total petroleum hydrocarbons (TPH) as diesel range organics, and residual range organics, and zirconium] have a low likelihood to become mobilized off-site due to the low rainfall in the area, lack of streams, and absence of a developed drainage system across the State-owned land.” 3-107 FEIS Vol I 3-112

The Final Environmental Impact Statement refers to a Phase II Environmental Condition of the Property (ECOP); however, that document does not appear in the Final EIS Supporting Documents or elsewhere in the publicly accessible administrative record.

Compound-by-compound scientific analysis exposes the distortionary and dangerous narrative the Army relies upon to minimize known contamination pathways and human health risks.

Antimony can become mobile under oxidizing conditions and through disturbance-driven dust and sediment transport. Its migration is not dependent on surface streams and is well documented at active and former firing and impact ranges.

Arsenic is a toxic metalloid whose mobility is highly sensitive to oxidation-reduction conditions, soil disturbance, and episodic rainfall events. Even when naturally occurring, arsenic can be mobilized from surface soils into groundwater and biota when land is repeatedly disturbed.

Cobalt is used in metal alloys and energetic materials and commonly co-occurs with explosive residues. It is readily mobilized when iron and manganese oxides dissolve, a process that occurs during wet-dry cycling and soil disturbance.

Copper The assertion that copper has a low likelihood of off-site mobilization due to low rainfall, lack of streams, or absence of engineered drainage is scientifically incorrect. Copper is primarily transported bound to fine sediments and organic matter and can be mobilized through erosion, dust, and episodic storm events—pathways that do not require perennial streams or developed drainage systems.

Iron The claim that iron has a low likelihood of off-site mobilization due to low rainfall, lack of streams, and absence of drainage infrastructure is scientifically unsound. Iron and iron-associated elements can be mobilized and redistributed through erosion of fine sediments, dust transport, and redox-driven geochemical processes, none of which require perennial streams or engineered drainage systems.

Lead is a well-established firing-range contaminant that migrates primarily through dust, erosion, and fine particulate transport. Its movement off-site has been documented at numerous military installations regardless of average rainfall or drainage infrastructure.

Manganese The claim that manganese has a low likelihood of mobilizing off-site due to low rainfall, lack of streams, or absence of drainage infrastructure is inaccurate. Manganese is part of dynamic environmental cycles and can be mobilized and transported through wind-blown dust and particulate matter, soil erosion, and atmospheric deposition, none of which require perennial streams or engineered drainage systems.

Selenium exists in highly mobile forms and readily migrates through soils under oxidizing conditions. It bioaccumulates and biomagnifies, making even low-level mobilization environmentally significant.

Silver is associated with munitions and pyrotechnic residues and is primarily transported via fine particles and dust. Wind-driven and disturbance-related transport pathways are sufficient to move silver off-site.

Zirconium is commonly used in munitions alloys and pyrotechnics and serves as an indicator of ordnance-related contamination. While less mobile than some metals, its presence confirms explosive sources rather than benign background conditions.

1-Methylnapthalene is a semi-volatile petroleum hydrocarbon that can volatilize, sorb to dust, and migrate during storm events. Its transport occurs through air and soil pathways, not solely through surface water.

Napthalene is highly volatile and readily migrates from soil to air, creating inhalation and vapor-intrusion exposure pathways. Its mobility is independent of rainfall, streams, or engineered drainage systems.

Total Petroleum Hydrocarbons (TPH – Diesel and Residual Range Organics)

TPH represents a mixture of hydrocarbons with varying mobility, toxicity, and persistence, including semi-volatile and carcinogenic fractions. Treating TPH as a single, immobile substance obscures real exposure and transport risks.

By asserting that this diverse suite of metals, metalloids, and organic contaminants has a “low likelihood” of off-site mobilization, the Army substitutes pseudo-scientific, generalized assumptions for compound-specific fate and transport analysis. Many of these contaminants migrate through dust, sediment, redox cycling, volatilization, and episodic storm events. These are pathways entirely independent of average rainfall, surface streams, or engineered drainage. This unsupported conclusion obscures well-established mechanisms of contaminant transport and fails to provide the disclosure required for informed decision-making under Hawaiʻi environmental law.

We have also witnessed the Army’s bull-headed refusal to recognize the propensity of PFAS compounds like PFOS to attach to minute particulate matter and become airborne. They appear to be living in their own scientific universe.

Chromium is mentioned in passing, as a part of studies.

Lead – “Potential lead and other contaminants associated with the use of military munitions would continue to accumulate in soils at firing points and ranges, and surface water flow and wildfires would continue to represent potential pathways for contaminant mobilization. Because there are limited surface water and groundwater pathways on the State-owned land and impact area, which is U.S. Government-owned land, and the Army would continue to follow range debris cleanup management procedures, the risk of contaminants mobilizing is limited.” FEIS Vol I 3-123

The Army must be living in a parallel universe. The Army’s claim that lead from munitions poses only a “minor” and “limited” risk is inconsistent with decades of scientific evidence and the Army’s own experience at other ranges. Lead does not degrade, dissipate, or become inert over time; it accumulates in soils at firing points and impact areas, where repeated use can drive concentrations into the thousands of parts per million. Hawaiʻi’s high-permeability volcanic soils, intense rainfall, surface runoff, and frequent wildfires increase, rather than limit, the mobilization of lead and associated metals into surface water and groundwater. The assertion that there are “limited pathways” ignores well-documented mechanisms such as erosion, ash transport, dust inhalation, and dissolved transport under changing redox conditions.

The following statements from the Army suggest either a disregard for well-established scientific principles or an assumption that the State would not rigorously scrutinize the Army’s claims. The deficiencies are sufficiently apparent that even a basic review reveals their flaws, raising serious questions about the level of scientific care applied in preparing the FEIS.

The Army - Debris from artillery training is contained within PTA training areas, ranges, firing points, and impact areas that are not open to the public and are closely monitored by the Army. The Army monitors the potential for offsite migration of contamination under the Operational Range Assessment Program and has determined groundwater and surface waters are unlikely to be contaminated by explosive residues. FEIS Vol II D-20

This is ridiculous, especially when the Army won’t share data.

The Army – “The closest drinking water well is 4,260 to 4,280 feet deep at the Waiki‘i Ranch (14 miles from PTA’s main gate). The state monitors all drinking water sources for water quality.” FEIS Vol II D-20

The argument that contamination does not pose a significant risk because the nearest current drinking water well is 14 miles away and more than 4,200 feet deep is not a defensible standard under the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA). Environmental impact analysis must consider possible future uses.

The Army – “Since August 1989, the State of Hawai‘i Department of Health has issued “Groundwater Contamination Maps” for Hawai‘i. According to these maps, most of the well locations where contamination is detected on the island of Hawai‘i are located along the eastern coast, and groundwater quality generally diminished towards the coasts due to increased saltwater intrusion.” FEIS Vol II D-20

The Army muddles coastal groundwater conditions with inland hydrogeology. The Army cites statewide “Groundwater Contamination Maps” showing contamination concentrated near the coast and diminished quality due to saltwater intrusion, then uses this to assert that inland groundwater beneath State-owned land is “likely of higher quality.”

The Army – “Detected contamination levels are below federal and state drinking water standards and do not pose a significant risk to humans.” FEIS Vol II D-18

The FEIS contains no analytical groundwater dataset that would allow a reviewer to independently verify the Army’s claim..

The Army – “Groundwater quality beneath the State-owned land is likely of higher quality due to its distance inland from the coast. The EIS provides additional information available on groundwater resources on the State-owned land. Two small-diameter holes were drilled for testing within the U.S. Government-owned land at PTA and were not designed to develop potable water. A non-aerially extensive perched aquifer was encountered in the test hole drilled near the main base at a depth of between 700 to 1,181 feet below ground surface. A more aerially extensive perched aquifer is believed to be present at approximately 1,800 feet below ground surface below the State-owned land. PTA is a remote facility, there are currently no plans to develop potable water within the State-owned land. Potable water is currently trucked to PTA from 40 miles away.” FEIS Vol II D-18

A perched aquifer is a shallow body of groundwater that sits above the main aquifer, separated from it by a layer of low-permeability material such as clay, or volcanic ash. The perched aquifer at Pohakuloa is vulnerable to contamination because it is shallow and directly connected to toxic military surface activities.

The Army acknowledges encountering perched aquifers at depths between 700–1,181 feet and a more extensive perched system at approximately 1,800 feet, yet dismisses their significance because the test holes were not designed to produce potable water? Is that it?

Identifying these aquifers without characterizing their water quality, connectivity, or vulnerability to contamination contradicts established best practices. This is a critical failure. Perched aquifers are well-documented conduits for contaminant transport and serve as recharge pathways to deeper aquifers.

Speaking of perched aquifers, the Army has historically used large-capacity cesspools at PTA.

We gained a sense of cesspools earlier in this report when we read that FEIS states that the Army continues to rely on cesspools and likely will be permitted to do so until 2050, unless legislation is passed to change this.

Cesspools are a Neanderthal-era method of waste disposal, little more than a hole in the ground where human and toxic wastes are dumped and left to seep untreated into surrounding soil and groundwater. Like cave dwellers digging a trench outside their shelter, cesspools rely on gravity and the porous earth to disperse sewage. There is no containment, no meaningful filtration, and no treatment of pathogens, nutrients, or synthetic chemicals. It is entirely incompatible with the protection of drinking water aquifers.

For years, the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency warned the Army that its continued use of cesspools on Hawaiʻi Island posed an unacceptable threat to groundwater and violated basic public-health protections, yet the Army resisted, delayed, and minimized the problem. EPA orders to inventory, permit, and ultimately close these primitive waste disposal systems were met with foot-dragging and procedural deflection, even as untreated sewage continued to percolate directly into some of the most permeable volcanic geology on Earth. The Army’s belligerence—treating cesspool closure as an administrative inconvenience rather than an urgent environmental hazard—left regulators repeatedly sounding the alarm while contamination risks persisted beneath State lands and downstream communities.

Cesspools provide a way for PFAS and other toxins to hitchhike a subterranean ride to contaminate wells, streams and coastal areas. For Native Hawaiians, these water reserves are sacred resources. This spiritual connection is driving the Army off of the Big Island.

The history of cesspools at Pōhakuloa—and the Army’s belligerent resistance to shutting them down—reveals more than regulatory noncompliance; it exposes an institutional psychology. For decades, the Big Island’s training grounds functioned as the Army’s personal proving ground, a vast colonial landscape where it could detonate weapons, dump waste, poison people, and externalize risk without adult supervision. This is how the Army has operated everywhere. Fort Ord, California; Aberdeen Proving Ground, Maryland; Anniston Army Depot, Alabama. The names change, but the pattern is consistent: catastrophic contamination, delayed accountability, and regulators trained to defer rather than confront. For generations, states and the EPA largely served as rubber stamps while the Army exercised free reign over land it did not own and communities it did not answer to. The cesspools were an exception to the rule.

There is no record indicating a prior U.S. state government has formally rejected a federal military environmental impact statement in the way Hawaiʻi’s Board of Land and Natural Resources (BLNR) has done in 2025, making this an extraordinary, unprecedented, action.

What is happening in Hawaiʻi is deeply threatening to the Army’s worldview. For the first time, a state has drawn a line and refused to ratify the fiction that military necessity excuses permanent environmental ruin. Sources close to the command say the Army is not particularly worried—not because it is confident in its pseudo-science, but because it assumes ultimate power will prevail. If pushed, they believe the federal government will simply seize the land through condemnation. That’s their ultimate trump card.

The Army is blowing toxic smoke. It must be stressed that across Volumes I, II, and III of the Army’s FEIS, there are no tables listing groundwater contaminant concentrations (e.g., PFAS, explosives, perchlorate, VOCs, metals) beneath the state-owned PTA lands. There are no sampling results expressed in units, like µg/L, ppb, ng/L, ppt. There is no identification of the location of specific wells, borings, or monitoring points with analytical data.

Without current baseline data, the BLNR concluded that the Army could not adequately assess the magnitude of environmental impacts, nor could decision-makers meaningfully compare alternatives. The reliance on future studies deprived the Board and the public of critical information needed to understand the environmental consequences of continued military occupation of public trust lands. BLNR p. 10

The BLNR’s 5–2 vote to reject the Army’s Final Environmental Impact Statement for Pōhakuloa Training Area reflects a determination that the document failed to meet the disclosure and analytical requirements of Hawaiʻi law.

To conclude, the FEIS did not fully evaluate impacts in the federally owned impact area, relied on incomplete and outdated data, failed to disclose the full range of environmental implications and responsible scientific opinion, inadequately addressed impacts to biological resources, and omitted critical analysis of cleanup obligations. Until these deficiencies are remedied through comprehensive, transparent, and scientifically robust analysis, BLNR concluded that acceptance of the FEIS—and renewal of the Army’s lease of state public trust lands would be legally and environmentally unsound.

===========================================================================================================

This project is supported by financial assistance from the Sierra Club of Hawaii.

Please consider donating to the Sierra Club of Hawai’i. Your donation will continue efforts to achieve Hawaiʻi’s 100% renewable energy goal, defend our oceans and forests, and build a more self-reliant and resilient community that prioritizes justice, enhances natural and cultural resources, and protects public health over corporate profit. Donate Here.