PFAS at the Pōhakuloa Training Area and the Kilauea Military Reservation, Hawaii

An analysis of the Final Preliminary Assessment and Site Inspection (PA/SI) of Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, Pōhakuloa Training Area and Kilauea Military Reservation, Hawaii, July 2023

This is Part 2 of a 6-part series. See Part 1 - The Army Is Quietly Walking Away from Oʻahu to Gain Leverage over the Pōhakuloa Training Area

By Pat Elder

January 14, 2026

An artist’s rendition of PFOS - 8 black carbon atoms, 16 green fluorine atoms, 1 yellow sulfur atom, 3 red oxygen atoms, and one white hydrogen atom.

The Pōhakuloa Training Area is profoundly impacted by PFAS contamination. This shouldn’t be surprising, although Army press releases and news coverage have been lacking.

The Army’s PFAS Preliminary Assessment/Site Inspection process reflects a systemic narrowing of scope that minimizes the extent of contamination across Army installations. Rather than evaluating the full range of documented PFAS uses, the Army largely confines its investigations to aqueous film-forming foam, (AFFF).

Even within this constrained focus, many AFFF-associated locations are downplayed or eliminated through sketchy interviews with installation subordinates and paper-based screening. This allows stormwater runoff, cesspool and leach-well reliance, and secondary transport mechanisms to be overlooked. The resulting portrayal of PFAS risk conflicts with the intent of CERCLA’s Preliminary Assessment / Site Inspection process, which is to identify all potential sources of release and exposure pathways.

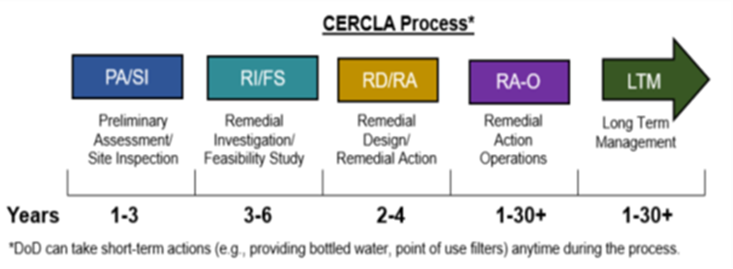

The Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act (CERCLA) establishes the Preliminary Assessment/Site Inspection process as a broad, screening-level inquiry designed to identify all areas of potential contaminant release, (in this case – PFAS) at a facility. Its purpose is not to confirm the absence of risk through selective analysis, but to ensure that incomplete information, uncertainty, and multiple potential sources trigger further investigation rather than premature closure.

While aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF) is a major contributor to PFAS contamination, elevating it as the only source constitutes a regulatory failure that obscures the Army’s multiple uses of PFAS across military installations and undermines the intent of environmental oversight laws.

Aqueous film-forming foam, (AFFF) is laced with PFAS and was historically used by Army fire department personnel for practice training exercises. They typically dug a pit that was about 50-100 feet in diameter and a few feet deep. They’d fill the crater with jet fuel and other combustibles and ignite it. Then, firefighters would extinguish the flames with the carcinogenic foam. They likely used thousands of gallons of AFFF concentrate and injected it into the heart of the Big Island.

The Pōhakuloa Training Area had a designated AFFF training area, and foam was used at the Bradshaw Army Runway. There were two generations of fire pits, as well as Building 39 Fire Station and the Building 390 Fire Station where AFFF use was documented. Foam use was routine and institutional.

The Army claims that “a former pit was used from an unknown date until 1984 and a newer pit was constructed in 1984 and operated until 2003.” The statement that the first pit was used until 1984 from an unknown date is a classic Army minimization tactic. If the pit pre-dated 1984, it almost certainly dates to the very early 1970s. If AFFF training began in the early 1970s, as it did almost everywhere there was a large military installation with training exercises and a runway, then 10–15 years of foam use are effectively erased from the record. Those years likely involved the deadliest PFOS-dominant formulations. This is not a data gap—it is a systematic undercount.

The U.S. Navy and the Air Force began PFAS environmental testing at military bases once standardized analytical methods were available (2009), with systematic PFAS sampling becoming common by the mid-2010s. The Army didn’t get into it until years later, after learning lessons from the upheaval experienced by the Navy and the Air Force.

The scant soil testing we have at PTA shows soil contamination is dominated by PFOS, perhaps reflecting “legacy” foam formulations prior to 2001 or so. This PFOS dominance may also reflect the environmental transformation of PFAS precursor compounds, which can degrade or biotransform over time into terminal perfluoroalkyl acids such as PFOS.

The Army’s account of AFFF use at PTA is not consistent with its own historical firefighting doctrine, the infrastructure it built, or the contamination patterns observed across comparable installations. As we have seen, AFFF training was routine by the early 1970s and commonly conducted monthly at bases with fire pits and airfields. The claimed frequency and volumes at PTA are implausibly low and appear designed to understate total releases rather than document them.

Areas of Potential Interest (AOPI’s)

Areas of Potential Interest (AOPI’s) have been repeatedly used by the Army as a screening tool to eliminate dozens of areas and a host of applications from further PFAS investigation. In practice, the table below functions less as a summary and more as a gatekeeping mechanism, allowing the Army to prematurely dismiss sites where PFAS use is plausible but not explicitly tied to aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF).

This approach reflects a systemic narrowing of scope within the Army’s PFAS Preliminary Assessment/Site Inspection process. Rather than evaluating the full range of documented PFAS uses across sprawling military installations, the Army centers its PFAS investigations on AFFF-related activities. At PTA, just five sites advanced to the remedial investigation phase of the CERCLA process.

This practice undermines the intent of CERCLA’s PA/SI process, which is to identify all areas of potential release, not merely those that align with the Army’s preferred narrative of limited exposure pathways. Let’s look at it.

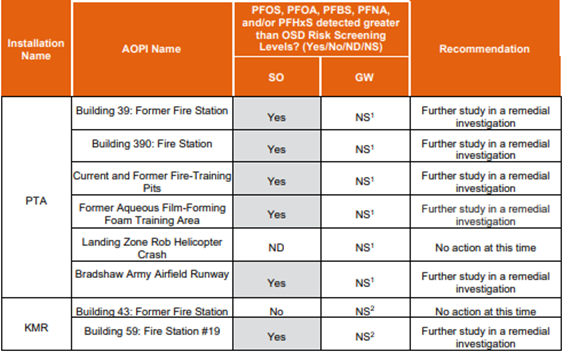

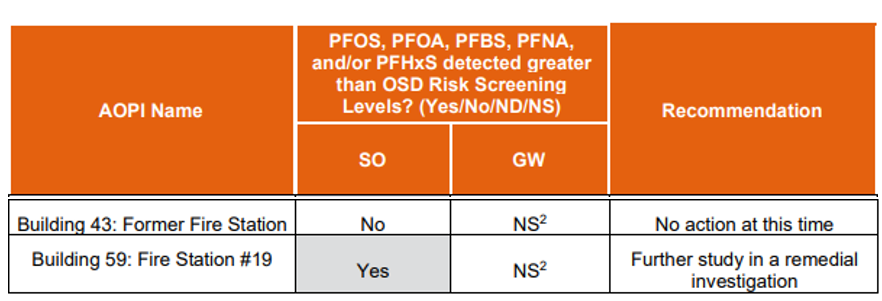

Table ES-1. Summary of AOPIs Identified during the PA, PFOS, PFOA, PFBS, PFNA, and PFHxS Sampling at PTA and KMR, and Recommendations

PTA is Pōhakuloa Training Area; KMR is Kilauea Military Reservation. We’ll look at it later. All of the “Areas of Potential Interest” or AOPIs, are related to AFFF. “SO” stands for soil. “GW” is groundwater. NS is not sampled. “Recommendation” designates the site’s standing in the CERCLA process, described below. The polluter decides the recommendations.

Under the current CERCLA implementation, the polluter is effectively allowed to decide what warrants further investigation. The same Army entity that caused the contamination defines the scope of inquiry and recommends whether additional action is necessary. This arrangement places the determination of potential liability in the hands of the party most exposed to cleanup costs, creating an inherent and structural conflict of interest.

The EPA has effectively ceded its oversight authority under CERCLA to the Department of Defense, allowing the Army, in this case, to define the scope, pace, and conclusions of PFAS investigations through narrowly framed PA/SI reports. Only a small fraction of contaminated sites are analyzed while things that ought to take a few weeks take a few years

By accepting limited sampling, delayed progression beyond the PA/SI stage, and “no further action” determinations despite acknowledged data gaps, EPA undermines CERCLA’s precautionary intent and permits long-term contamination to persist without meaningful accountability or remediation.

Hawaii is on its own.

The Army’s decision to test for only five PFAS compounds—PFOS, PFOA, PFBS, PFNA, and PFHxS during the Site Inspection at Pōhakuloa Training Area should be a source of deep concern, because it captures only a fraction of the PFAS universe known to contaminate military sites. These compounds are commonly referred to as “terminal PFAS” because they are the end products of environmental and biological transformation of many PFAS precursors.

EPA Method 1633, now the standard analytical method for PFAS in environmental media, is capable of detecting 40 individual PFAS compounds, including many that are shorter-chain, more mobile, and increasingly used as replacements for legacy chemicals. Limiting analysis to five compounds creates the false impression that PFAS contamination is limited, when in reality the method itself acknowledges a much broader chemical footprint.

Even more troubling is that Method 1633 does not directly capture PFAS precursors, which are also toxic in their original form.

Many precursors were used by the military in firefighting foams, surface treatments, corrosion inhibitors, pesticides, and industrial formulations. Today, more than 16,000 distinct PFAS compounds exist.

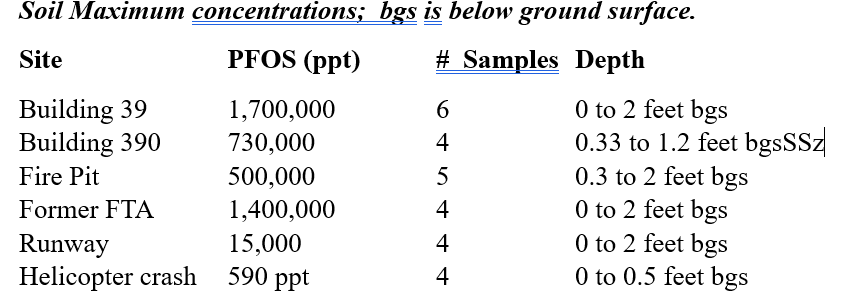

We saw from the graphic showing the Areas of Potential Interest that the Army failed to test groundwater. They did take soil samples from the 6 AOPIs. The extraordinarily high concentration of PFOS in the soil at these sites represents a serious threat to the environment and human health. The following chart shows the 6 sites and their maximum PFOS soil concentrations.

Soil Maximum concentrations; bgs is below ground surface.

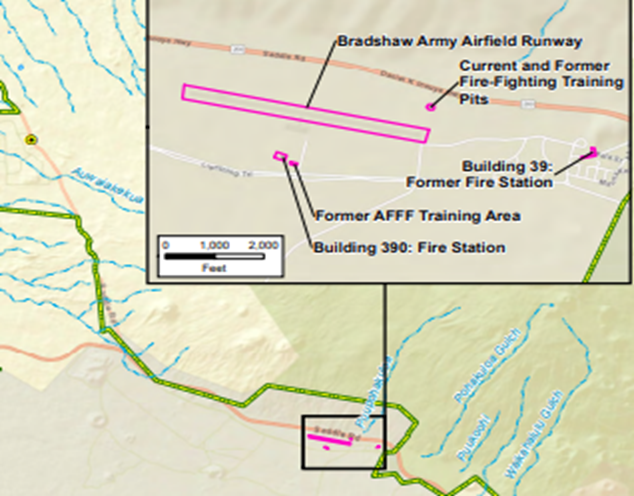

All five of the areas of potential interest are identified in this graphic. - Figure 5-2 PTA AOPI Locations

PFOS concentrations at these levels in shallow soils pose a clear human health risk because PFOS readily migrates from soil into groundwater, can be transported by stormwater, and can become airborne on fine dust that is inhaled or ingested. Because PFOS bioaccumulates and persists in the human body for years, even intermittent exposures can contribute to long-term risks including immune suppression, thyroid disruption, elevated cholesterol, and increased cancer risk.

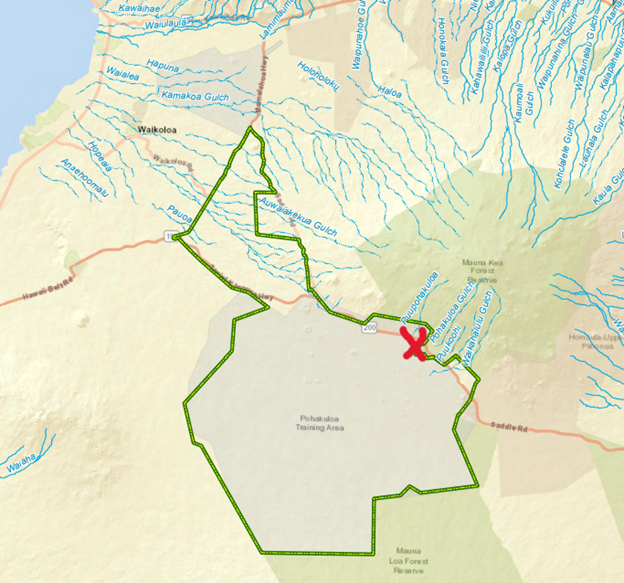

The red X shows the highly contaminated area on a regional map. The training area is located southeast of Maona Kea

Building 39 - Former Fire Station is identified as an area of potential interest due to historical use of AFFF. The former fire station was operational from 1969 through approximately 1996. AFFF was stored throughout the interior and exterior of the building. The buckets of AFFF were stacked vertically, which, according to the Army, frequently resulted in the bottom buckets becoming cracked due to the weight of the buckets above. Fire trucks were filled with AFFF on the fire station apron. Truck maintenance activities were also conducted at the station. Newly graded material was present at the offsite drainage area, so, a deeper, composite subsurface soil sample was collected from a sampling location from a 2- foot interval of native material located up to 3 feet down. This is important because it allowed soils with higher concentration of PFAS to be examined and it suggests that the deeper the sample, the higher the concentration, at least for some distance.

The Army removed the 35-acre Schofield Barracks landfill from further PFAS evaluation after reporting no detections in shallow soils. This result was expected. Following closure of the landfill in 1981, a 2 foot - 2.5-foot-thick compacted soil cover was installed over the waste. The Army nonetheless relied on two soil samples collected from 0–2 feet below ground surface—within the cover material itself—and reported no detections of PFOS, PFOA, PFBS, PFNA, or PFHxS. On that basis alone, the landfill was screened out, and no further investigation was proposed.

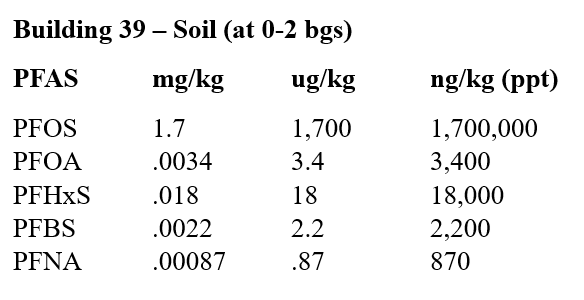

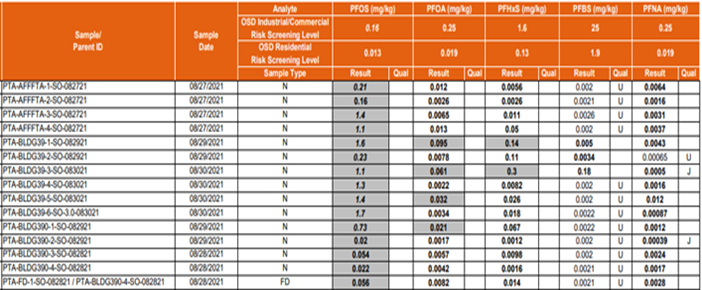

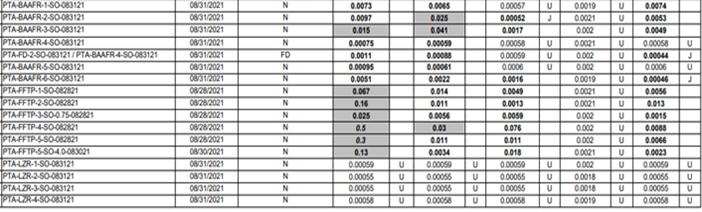

Let’s look at PFAS concentrations at Building 39 at the Pōhakuloa Training Area

______________________________________________________________________________________________________________

The Army has reported 1.7 million parts per trillion of PFOS in soil at the Pōhakuloa Training Area.

EPA PFOS Soil Screening Levels are Bogus

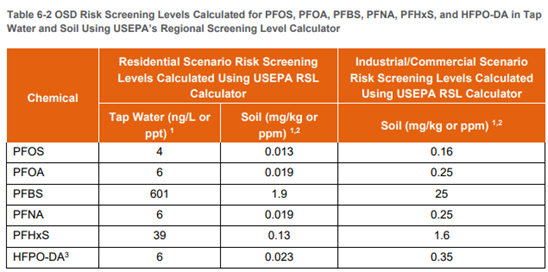

The U.S. Army’s soil screening level for PFOS is set at 160,000 ppt. See Table 6-2, here. .16 ppm = 160,000 ppt.

The Army (and DoD more broadly) adopts and relies on EPA’s Risk Screening Levels to decide whether further investigation is warranted. In the case of Building 39, the PFOS levels exceeded the RSL’s, so the site advanced in the CERCLA process to the remediation stage.

In practice, however, the Army uses the EPA’s Risk Screening Levels as a procedural justification to screen out PFOS-contaminated soils and narrow the scope of CERCLA response actions.

To put these standards into perspective, Germany has binding PFAS assessment guidelines that regulate both groundwater and the soil–to–groundwater pathways. This is something the EPA and it “partner” the Army, do not seriously pursue. Under these guidelines, PFOS in groundwater has a “trigger value” of 100 ppt, the level at which remediation or further investigation becomes mandatory. Germany also regulates soil eluate, which is a laboratory test mimicking how contaminants leach out of soil into groundwater. For any soil to be reused or left in place without restrictions, PFOS in the soil eluate must be less than 100 ppt. If the eluate exceeds 100 ppt, the soil cannot be reused and is considered a threat to groundwater. Think of all of the PFAS in the soil at PTA like a giant coffee percolator. 100 ppt in Germany and 160,000 ppt in Hawaii..

1.7 million ppt PFOS in surface soil threatens human health. Any disturbance: wind, vehicles, grading, foot traffic, helicopter rotor wash, mowing, construction, etc., can generate PFOS-bearing dust and soil contact exposure for people in the area. PFOS strongly sorbs (attaches to the surface of another material) to fine soil particles and organic matter, allowing it to become airborne as contaminated dust when soils are disturbed by wind, vehicles, construction, or rotor wash. These particles can be inhaled and deposited in our lungs or settle indoors, where PFOS-contaminated dust accumulates in buildings and on surfaces, creating an ongoing exposure pathway even without direct soil contact.

Rains carry the concentrated carcinogenic soil into the subsurface. PFOS sorbed to fine sediment is carried in stormwater runoff into ditches and gulches, expanding the footprint downstream. Infiltration can also carry an indefinite supply of PFOS downward through fractured basalt and cinder layers, where it can accumulate in perched zones or deeper soil intervals. This raises concern that PFOS will eventually migrate into drinking water aquifers on an island with limited freshwater resources. It is truly frightening that these chemicals may poison the Big Island forever

Building 390

From the Army – “Building 390, the current fire station, was constructed in about 1983. AFFF has been stored throughout the interior and exterior of the building. From approximately 1992 to 1999, spills were known to have occurred from buckets stacked on the exterior of the building. In 2019, there were approximately 310 gallons (sixty-two 5-gallon buckets) of AFFF stored in a shed west of the station building. The AFFF had been purchased approximately 8 years prior. Historically, truck maintenance activities were conducted at the station (until approximately 1999), and fire trucks were filled with AFFF on the fire station apron.”

The Army’s claim that 62 five-gallon buckets of AFFF—purchased eight years earlier—were still being stored in 2019 is implausible given the documented operational reality. AFFF was a routinely used consumable at Building 390 and multiple nearby locations, delivered regularly by truck on pallets and used for vehicle filling, training support, and fire response. In that context, AFFF supply would have turned over continuously; it would not have remained unused for nearly a decade. The assertion that these buckets were stored this long minimizes the scale and frequency of AFFF handling and obscures the likelihood of ongoing use, transfers, and releases well beyond what is described as isolated spills.

The Army reported PFOS at concentrations of 730,000 ppt in soils at this firehouse at very shallow depths. That’s all we know. Tests a hundred feet away could have twice the levels, or half the levels. The DOD has been playing a shell game with the US public on PFAS testing of soils and groundwater.

Current and Former Fire Training Pits

The Army says in the PA/SI, “From 1992 to 1999, there were at least six to seven training events. During each event, 1,000 gallons of water and approximately 100 gallons of 3% AFFF were sprayed in a sweeping motion into the pit and the surrounding area. Liquid drained to nearby injection wells. Usage was likely less frequent before 1992 and after 1999. There have been no PFAS-containing materials used at the training pits since at least 2003. The Former AFFF Training Area was used for firefighting training one to two times per year from approximately 1999 to 2009 where foam was sprayed towards and into a brush-filled drainage ditch.”

Reality check

The claim that, from 1992–1999, there were only six to seven training events, each using roughly 1,000 gallons of water and 100 gallons of 3% AFFF is difficult to believe. By the early 1970s, the Army had institutionalized AFFF for crash-rescue training, live-fire training pits, and nozzle testing. A claim that PTA had only 6–7 events over seven years is inconsistent with Army-wide practice. Across Army, Navy, and Air Force installations, AFFF training typically occurred monthly.

A 2020 Army report on the use of PFAS at the Kalaeloa Airport claims that the Hawaii Department of Transportation Aircraft Rescue and Firefighting (ARFF) Unit regularly released aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF) containing PFAS during monthly exercises at the former fuel farm area at the airport. Firetrucks were fitted with foam tanks and hose sprayers containing the carcinogenic materials, according to the “Preliminary Assessment” report on Perfluoro Octane Sulfonic acid (PFOS) and Perfluoro Octanoic Acid (PFOA).

The tanks reportedly contained 25 gallons of AFFF concentrate mixed with water. The monthly pump tests occurred at random locations across Kalaeloa Airport.

Frequency of testing protocols

According to the 1999 Superfund Record of Decision, the Army’s Vint Hill Farms Station in Virginia, a firefighting training pit was used monthly. The pit was filled with petroleum and natural gas odorant. The unlined crater was approximately 50 feet in diameter and 3 feet deep. Solvents and other combustible materials were used in the pit.

Fire training at Fort Meade took place 12-15 times a year at various locations.

The Aberdeen Proving Ground Fire Department conducted nozzle-testing utilizing AFFF on a monthly basis at various firehouses.

Joint Base Andrews held weekly AFFF fire pit training for years, according to the PA/SI released in 2018. Generally, there was a much greater effort to earnestly report the contamination eight years ago, but that transparency has evaporated across all DOD installations.

The PTA PA/SI reports that firefighters used 100 gallons of 3% AFFF concentrate mixed into 1,000 gallons of water. This doesn’t make sense because using 100 gallons of 3% AFFF concentrate that is mixed properly means the system would discharge over 3,200 gallons of water, producing more than 3,300 gallons of foam solution onto the ground.

We can’t trust what the Army is telling us. If the Army used 100 gallons of concentrate monthly - and that use stretched back to 1970 when the practice became institutionalized, the period from 1970 until 2020 stretches over 50 years – or 600 months. (and this is only for one AFFF release area) 600 months x 100 gallons = 60,000 gallons of concentrate.

On November 29, 2022, the Navy released 1,300 gallons of AFFF concentrate at the Red Hill facility in Honolulu. Over the years, the release of AFFF at Pohakuloa might be 46 times this amount. Who knew?

The cumulative volume implied by the Army’s account is orders of magnitude lower than the quantity of AFFF used at similar facilities.

The Army’s own language undermines its claim. This is not surprising, considering the slipshod, contradictory format employed by the Army in its Final Environmental Impact Statement we saw in Part 1 of this series. It’s one of the main reasons the BLNR told them to take a hike.

Former FTA

The Army claims that the Former AFFF Training Area, located near the Bradshaw Army Airfield control tower, was used for firefighting training one to two times per year from approximately 1999 to 2009. Foam was sprayed towards and into a brush-filled drainage ditch. It is preposterous that the Army claims that firefighting training occurred just one or two times per year at the former fire training area when they reported 1.4 million ppt of PFOS on the site 17 years after the fact.

Landing Zone Rob Helicopter Crash The crash occurred in the late 1990’s. Although the crash did not generate a fire, the response included the use of 3,000 gallons of water and 90 gallons of AFFF. This represents a 3% mixture, unlike the previously described scenario. The sparse data we have from the site show surface soil concentrations for PFOS at 590 parts per trillion. The surface soil at Building 39 had a PFOS concentration of 1.7 million parts per trillion.

Bradshaw Army Airfield Runway

From 1992 to 1997, training exercises were performed on the Bradshaw Army Airfield Runway to empty PFAS-containing materials from fire truck reservoirs prior to performing truck plumbing maintenance. Training was performed throughout the runway; however, most of the training was likely conducted on the ends of the runway. Soil here had a PFOS concentration of 15,000 ppt.

Table 7-1 Soil PFOS, PFOA, PFBS, PFNA, and PFHxS Analytical Results USAEC PFAS Preliminary Assessment/Site Inspection Pohakuloa Training Area, Hawaii

It’s important to note that PFOS is not the only compound that was reported at PTA. Let’s examine the highest levels reported for PFOA, PFHxS, PFBS, and PFNA.

PFAS ppm ppt

PFOA .095 95,000

PFHxS .14 140,000

PFBS .18 80,000

PFNA .012 12,000

___________________________

Other sources of PFAS contamination

Groundwater at PTA

According to the Army, “Historical reports indicate groundwater at PTA has been identified several hundred to more than 1,000 feet below ground surface (bgs). The significant depth to groundwater precludes collection of groundwater samples as part of this SI; instead, soil samples were collected to verify the presence of PFAS at PTA.”

The State of Hawaii Commission on Water Resource Management has 13 deep monitoring wells across the state and some are drilled deeper than 1,000 feet.

There are no perennial surface water bodies like surface streams, lakes, or other bodies of water on PTA. The intermittent stream channels quickly dry after rainfall. The majority of soil is generally permeable; and, due to the relatively low rainfall and the high permeability of the soils and underlying bedrock, there are no perennial streams within 15 miles of the PTA installation.

Mauna Kea last erupted approximately 4,600 years ago, and that eruptive history shapes the geology of the Pōhakuloa Training Area today. PTA sits on volcanic deposits composed of fractured lava flows, cinder beds, and ash layers that are highly permeable. These materials allow rainfall and surface water to infiltrate rapidly, moving contaminants vertically and laterally through the subsurface rather than confining them near the surface.

Groundwater and the PFAS it carries can travel much faster and farther than in typical continental sedimentary aquifers. The actions of the Army at PTA have threatened the Big Island forever.

According to the PA/SI at PTA, at least seven intermittent streams drain surface water off the steep southwestern flank of Mauna Kea. Along the western boundary of the installation, the closest stream is Popolo Gulch, which converges with Auwaiakeokua Gulch to drain surface water toward the Waikoloa community. Within 2 miles of the cantonment area, three intermittent streams, Waikahalulu Gulch, Pōhakuloa Gulch, and an unnamed gulch, collect runoff from the southern flank of Mauna Kea. Waikahalulu Gulch and the unnamed gulch extend on and off post while Pohakuloa Gulch is completely off post.

Cesspools

The Army has historically used large-capacity cesspools at PTA. Cesspools are a Neanderthal-era method of waste disposal, little more than a hole in the ground where human and toxic wastes are dumped and left to seep untreated into surrounding soil and groundwater. The larger systems were legally required to be closed by 2016, and there is no public evidence that some smaller traditional cesspools remain in operation today. The Army has never been readily transparent regarding these sorts of things.

A Department of Defense procurement notice from late 2025 shows the Army intends to acquire a Presby Advanced Enviro-Septic (AES) wastewater treatment system for PTA, designed to treat pre-treated wastewater from 5,000 to 67,000 gallons per day. The new wastewater treatment plant will not treat for PFAS.

Pesticides

Aside from the PFAS used in firefighting foams, the Preliminary Assessment / Site Inspection for PTA lists former pesticide storage areas as preliminary locations for use, storage, and/or disposal of PFAS-containing materials.

From the PA/SI – “One building was identified as a potential storage area for PFAS-containing pesticides. During a telephonic interview with the IMCOM Pest Management Consultant, it was noted that products containing Sulfluramid (i.e., associated with insecticides) may have contained PFAS and were phased out in 1996.”

Sulfluramid’s scientific name is N-ethyl perfluorooctane sulfonamide, known as N-EtFOSA, a PFAS compound that degrades in the environment to deadly PFOS.

The Army used sulfluramid at PTA for routine pest control. PTA has long supported troop housing, cantonment areas, training facilities, storage yards, and administrative buildings in a dry, high-elevation environment where ants and termites are persistent problems.

The liquid PFAS was applied directly to soil around buildings, storage areas, and infrastructure. The Army did not need to document it as “PFAS use” because PFAS was not yet a regulated category. As a result, records are sparse, but the use pattern is entirely predictable for a large, permanently occupied Army installation like PTA.

Dismissing pesticide storage and application areas in the PA/SI due to a lack of “specific evidence” is scientifically indefensible. Sulfluramid degrades into PFOS, was applied directly to soil, and was used precisely in areas where long-term contamination would be expected. Its use explains PFOS detections outside firefighting areas and reinforces that landfills, storage areas, and routine base operations—not just AFFF—are credible PFAS source pathways at PTA.

Landfills

“Following the Preliminary Assessment site visit, information from interviews and acquired documents were reviewed and no specific evidence was identified confirming disposal of PFAS containing waste at these landfills.”

The Army’s assertion that “no specific evidence was identified confirming disposal of PFAS-containing waste” at PTA landfills reflects a failure of investigation, not proof of absence. Landfills on military installations are well-established repositories for PFAS, receiving decades of mixed wastes including firefighting residues, treated materials, packaging, contaminated soils, maintenance debris, textiles, and sludges. PFAS in landfills migrate into leachate, which is now widely recognized as one of the dominant pathways by which PFAS enter groundwater and surface waters. Treating landfills as implausible PFAS sources because of missing paperwork ignores both the chemistry of PFAS and the documented behavior of landfill systems nationwide, including at other Army installations.

Under CERCLA, Areas of Potential Interest are supposed to be evaluated based on credible release mechanisms and known contaminant behavior, not on whether the polluter kept records. At PTA—where permeable volcanic geology accelerates subsurface transport—failing to investigate landfills and pesticide areas virtually guarantees that PFAS pathways will be permanently written out of the remedial process.

AFFF used on Wildfires?

Interviews conducted during the PFAS Preliminary Assessment (4.1.3 Readily Identifiable Off-Post PFAS Sources) indicate that the PTA Fire Department may have used aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF) during off-post wildfire responses at the request of Hawaiʻi County.

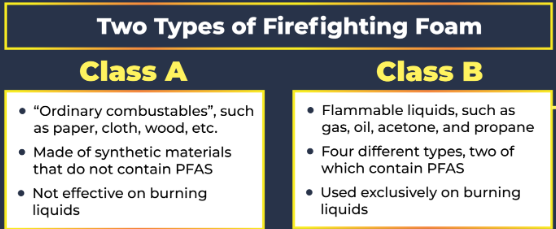

This raises serious questions regarding compliance with longstanding Department of Defense firefighting policy, which clearly distinguishes between Type A foams, intended for Class A fires such as brush and wildland fires, and Type B foams, including AFFF, intended for Class B petroleum-based fires. AFFF was designed to suppress fuel fires and was not operationally appropriate for vegetation fires, where it provides little benefit compared to water or Type A foams.

The use of AFFF on wildfires would therefore represent a misapplication of firefighting agents rather than an operational necessity. Mutual aid or off-installation response does not suspend DoD environmental or operational requirements, nor does it transfer responsibility for chemical releases to the requesting jurisdiction. If AFFF was deployed during wildfire suppression, the discharge would constitute an uncontrolled environmental release of PFAS into open terrain, where runoff, ash redistribution, wind transport, and infiltration into fractured volcanic substrates could occur—conditions fundamentally different from controlled applications at training or crash-response sites.

Most critically, this information appears only in interview summaries within the PA and is not disclosed, evaluated, or analyzed in the FEIS. The FEIS discusses wildfire occurrence and suppression at PTA in detail, yet omits any assessment of suppression agents used during those responses. If AFFF was used during wildfires, this represents a credible PFAS source pathway that was neither disclosed nor analyzed, undermining the completeness of the environmental review and reinforcing concerns that the FEIS failed to fully evaluate foreseeable environmental impacts associated with ongoing and historical military operations.

Additional potential release areas or pathways to human ingestion not pursued by the Army.

Battery shops Fluoropolymers and fluorinated elastomers are widely used in cable insulation, wire jacketing, gaskets, seals, and coatings.

Bioaccumulation in birds, mammals The Army’s PA/SI at Pōhakuloa Training fails to evaluate bioaccumulation of PFAS in birds and mammals, an omission that ignores a well-established exposure pathway whereby PFAS concentrate up the food web—particularly in predatory and migratory species.

Contaminated backfill used for construction elsewhere on base has not been documented in the PA/SI.

Firing ranges Firefighting foams containing PFAS were commonly deployed on Army facilities for fuel-related fires involving vehicles, generators, or spill incidents, that are common at active ranges.

Fuel spills containing fluorinated surfactants were common at training facilities.

Hangar floor drains The PA/SI does not evaluate hangar and maintenance-bay floor drains, which at facilities like Pōhakuloa Training Area commonly receive AFFF-impacted wash-down and fire-response water and can serve as conduits transporting PFAS into sewer, cesspool, or leach systems—an omission that leaves a significant potential release pathway unexamined.

Pyrotechnics, flares, and obscurants used on ranges typically contain fluoropolymers which are manufactured using PFAS.

Stormwater runoff at PTA flows to downgradient drainage ditches. The drainage ditches are not connected to any perennial water bodies that flow off-installation. Due to the high permeability of the soils and underlying bedrock, stormwater runoff likely quickly recharges groundwater.

Sewer System - PTA has historically used cesspools to manage untreated, raw sewage. Cesspools were not tested for PFAS.

Furthermore, these locations are known to be sources of PFAS

but they are not addressed in the PA/SI.

Laundry effluent Photo labs

Repair shops Petroleum, Oil, Lubricant Areas

Warehouses Sub-Slab Vapor Intrusion

Transformer leak areas Underground storage tanks

Vehicle maintenance Vehicle scrap yard

Vehicle Wash racks Weapons storage areas

______________________

Conclusion

What emerges from the Army’s own data, despite decades of minimization, selective testing, and regulatory sleight of hand, is a portrait of permanent contamination at the heart of Hawaiʻi Island. Pōhakuloa is not marginally impacted; it is saturated with PFAS at concentrations so extreme that they would trigger emergency action in many countries with modern environmental safeguards. Millions of parts per trillion of PFOS in surface soils, undisputed pathways to groundwater in fractured volcanic geology, unexamined cesspools, landfills, pesticides, and wildfire releases, and the deliberate refusal to test groundwater together form a reckless experiment conducted on an island with finite freshwater and no escape valves. The Army has used uncertainty as a weapon, narrowing the scope of inquiry until the contamination appears manageable, while the chemicals themselves continue to migrate, bioaccumulate, and persist - perhaps forever. This is not a legacy problem that will fade with time. It is a growing, irreversible threat to ecosystems, drinking water, and human health that will outlive the institutions that caused it. If allowed to stand, the PTA PFAS record will become a case study in how regulatory failure and military privilege can poison a place permanently, leaving future generations to bear the costs of today’s denial.

PFAS Contamination and Incomplete Site Characterization at Kīlauea Military Reservation (KMR), Hawaiʻi

An analysis of the Final Preliminary Assessment and Site Inspection (PA/SI) of Per-and Polyfluoroalkyl Substances, Pōhakuloa Training Area and Kilauea Military Reservation, Hawaii, July 2023

The Red X on the left shows Building 59 while the red X on the right shows Building 43. They are both areas of AFFF use by the Army on the Kīlauea Military Reservation.

Kīlauea Military Reservation (KMR) occupies approximately 54 acres on the northern rim of Kīlauea Crater within Hawaiʻi Volcanoes National Park on the island of Hawaiʻi. It is approximately 30 miles southwest of Hilo. Although the Army currently characterizes Kīlauea Military Reservation as primarily recreational, available Army records show the facility has functioned as a residential facility for roughly eight decades. Today, the installation functions as a recreational and lodging facility serving active-duty and retired military personnel, reservists, and Department of Defense civilians. Kīlauea Military Reservation contains approximately 90 cottages and apartments that operate as hotel-style lodging.

The distinction between a residential and a recreational installation is critical because it determines both the intensity and continuity of contaminant sources and the assumptions regulators make about exposure duration and pathways. A recreational facility implies intermittent, short-term occupancy with limited infrastructure and minimal domestic waste generation, whereas a residential facility reflects continuous human presence over decades, with associated wastewater systems, fire protection, vehicle maintenance, fuel storage, cleaning products, furnishings, and consumer goods that cumulatively introduce a far broader suite of contaminants into the environment.

In the context of PFAS, this distinction is important because residential releases the toxins through sewage systems, septic tanks, cesspools, laundering, and routine fire-suppression readiness. These are pathways that are largely absent at purely recreational sites. By characterizing Kīlauea Military Reservation as recreational rather than residential, the Army narrows the conceptual site model and minimizes chronic exposure potential.

Areas of Potential Interest, (AOPIs)

SO is soil; GW is groundwater; NS is not sampled. Only Building 59 will be further investigated for PFAS.

The Army’s PFAS Preliminary Assessment/Site Inspection (PA/SI) identifies two Areas of Potential Interest (AOPIs) at Kīlauea Military Reservation associated with aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF) use: Building 43, the former fire station that operated from 1942 to 1994, and Building 59, which has operated since 1994 (USAEC, 2023).

AFFF was historically stored and used by fire department personnel (from 1970 onward) to fill fire trucks at the Building 43, the former Fire Station from 1942 until 1994. The Kīlauea Military Reservation Fire Department moved its operations to the Building 59: Fire Station #19.

While the Army documents the storage of AFFF and the presence of AFFF-equipped fire trucks, it does not describe how or why the foam contained in those vehicles was routinely discharged. At military installations nationwide, AFFF-equipped fire trucks commonly participated in nozzle testing, system checks, hose flushing, and training exercises, all of which required periodic discharge of foam solutions and resulted in intentional releases to pavement, soil, or fire training areas.

The absence of any discussion of these routine fire-protection practices at Kīlauea Military Reservation represents a significant gap in the Site Inspection record, effectively treating AFFF as a static material rather than a consumable agent that is regularly discharged. This silence obscures a source of repeated PFAS releases over decades of continuous fire station operations at the installation.

Building 43 housed two fire trucks, each containing 60 gallons of AFFF. Four or five 5-gallon pails of 3% or 6% AFFF were stored within the building during a 1990 U.S. Army Toxic and Hazardous Materials Agency assessment. Fire trucks were filled with AFFF on site, and vehicles containing AFFF were routinely washed on a concrete apron.

The fire station bay had a concrete floor with no drains, and wash water generated during vehicle cleaning flowed onto adjacent paved roadways that lacked storm drains or sewer infrastructure. The Army assumes that this rinse water “likely evaporated,” despite the absence of any empirical evaluation of infiltration, runoff, or subsurface transport.

Building 59 was used to store AFFF and fire trucks containing AFFF were washed on the station apron or driveway. Prior to approximately 2009, when a trench drain was installed on the station apron, the apron and station bays were known to flood during heavy rains. The trench drains discharge to a grassy area southwest of the station. According to firefighting staff, since at least 2009, no PFAS-containing materials have been used at KMR, including for training; however, one 5-gallon pail of AFFF was at the station during the PA site visit.

Improper Elimination of Groundwater as a Migration Pathway

The PA/SI asserts that groundwater sampling was precluded because infiltrating water “turns to steam” due to a rapid increase in temperature with depth. This claim is unsupported by site-specific data. Assertions that infiltrated water subsequently “turns to steam” are not entirely supported by hydrologic or geothermal literature.

Under CERCLA, groundwater must be evaluated as a potential migration and exposure pathway unless it can be demonstrably ruled out based on site-specific evidence. The reliance on unsupported assumptions to justify the absence of groundwater sampling represents a procedural failure that obscures potential long-term and off-site transport risks.

Contaminated Soil

PFOS is reported to have concentration of 12,000 parts per trillion (ppt) in the soil at Building 43 and 57,000 ppt at Building 59. 57,000 ppt PFOS in surface soil (57 µg/kg, or 0.057 mg/kg) is a fraction of the 1.7 million ppt at the Pōhakuloa Training Area, but it’s still a serious indicator of an AFFF-impacted source area.

Contaminated soil at this concentration may become airborne to settle in the lungs of people nearby. It may settle indoors as dust to threaten infants and toddlers.

Wastewater Management and PFAS Pathways

According to interviews conducted during the PA/SI site visit, Kīlauea Military Reservation historically relied on cesspools for sewage disposal until approximately 1984, when they were replaced with septic tanks. Portable toilets are also used throughout the installation for sanitary waste disposal (USAEC, 2023).

As we have seen, cesspools function as direct subsurface discharge systems that release untreated wastewater into surrounding soils and fractured rock. In volcanic terrains, cesspools act as de facto injection points, allowing dissolved contaminants and particulate-bound compounds to freely enter the subsurface. PFAS introduced into these systems through domestic wastewater, wash water, or contaminated dust would have been discharged directly into the subsurface for decades prior to conversion to septic systems.

Septic systems do not eliminate PFAS contamination but redistribute it between liquid effluent and accumulated solids. Numerous studies have demonstrated that both long- and short-chain PFAS, as well as polyfluorinated precursor compounds, partition into septic tank sludge and septage. Septic effluent therefore represents a continuing on-site PFAS loading mechanism, while sludge removal transfers PFAS off-site to wastewater treatment plants, landfills, or land-application facilities, where it may persist or re-enter the environment through biosolids reuse or leachate generation. We don’t know where it is sent or what happens to it.

In a remote installation lacking centralized wastewater treatment, sewage sludge represents one of the most plausible long-term PFAS redistribution mechanisms, both on site and beyond installation boundaries.

Narrowing of the PFAS Inquiry

The PA/SI concludes that no additional areas of PFAS use, storage, or disposal were identified at KMR and that no PFAS-containing pesticides or insecticides were used or stored at the installation. This conclusion rests on limited records and contrasts with broader DoD documentation demonstrating widespread historical use of PFAS-containing products across military installations during the same period. By eliminating groundwater pathways, ignoring wastewater and sludge management, and assuming evaporation or containment without supporting data, the Site Inspection systematically narrows the scope of inquiry until contamination appears manageable by omission rather than analysis.

Conclusion

The Army’s own documentation demonstrates that Kīlauea Military Reservation has credible, unexamined PFAS migration pathways associated with documented AFFF use, rapid infiltration in fractured volcanic geology, historical cesspools, ongoing septic systems, and uncharacterized sludge disposal practices. The assertion that infiltrating water “turns to steam” and thereby negates groundwater concerns is unsupported by site-specific data and inconsistent with established Hawaiian hydrogeology.

Under CERCLA, uncertainty should trigger further investigation, not justify its avoidance. The refusal to sample groundwater and evaluate wastewater-related PFAS pathways at Kīlauea Military Reservation represents a discretionary narrowing of the Site Inspection that obscures long-term risks on an island with finite freshwater resources and no alternative supply. PFAS contamination does not dissipate with time; it persists, migrates, and bioaccumulates.

This project is supported by financial assistance from the Sierra Club of Hawaii.

Please consider donating to the Sierra Club of Hawai’i. Your donation will continue efforts to achieve Hawaiʻi’s 100% renewable energy goal, defend our oceans and forests, and build a more self-reliant and resilient community that prioritizes justice, enhances natural and cultural resources, and protects public health over corporate profit. Donate Here.