Tripler Army Medical Center in Hawai’i Evades PFAS Scrutiny

Its justifications for inaction stretch the bounds of scientific reason.

By Pat Elder

February 8, 2026

Tripler Army Medical Center, located approximately 4 miles northwest of downtown Honolulu, is contaminating the island of Oahu with PFAS.

Federal law requires the Army to identify and disclose a comprehensive inventory of PFAS-containing products and applications that it routinely uses, stores, and discards. Aside from the fire station, the Army has closed its investigation of PFAS at the sprawling complex.

As demonstrated at multiple Army facilities in Hawaiʻi, the Army is circumventing the intent of the law by narrowing its inquiry to a single PFAS application - firefighting foam, while ignoring dozens of other known PFAS uses, in industrial products, maintenance operations, and medical procedures.

The Fire Station at Tripler Army Medical Center will advance in the CERCLA process to the Remedial Investigation stage. CERCLA—the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, commonly known as Superfund—requires federal agencies to fully characterize contamination, assess exposure pathways, and address risks to human health and the environment. In theory, the statute imposes strict liability on responsible parties, obligating them to pay for cleanup or reimburse the government for doing so. In practice, the Army is selectively defining PFAS sources to constrain the scope of investigation.

This report will diverge from prior reports in this series by examining the pathology of institutional denial that underlies the Army’s dangerous and obstinate stance.

Consider these three “logical lapse” statements from the Medical Center’s Preliminary Assessment / Site Inspection:

Logical Lapse #1: “Given the considerable depth to groundwater at the installation, estimated to be 200 feet below ground surface, groundwater sampling was not included in the scope of the Site Inspection.”

Logical Lapse #2: “Given that the specific stormwater sewer route and discharge location for stormwater originating from AOPI Building 320: Fire Station #3 is undetermined from a review of readily available documents, off-installation surface water and sediment sampling were not included in the scope of the SI.”

Logical Lapse #3: “Soil samples collected from the area of potential interest would more accurately evaluate PFOS, PFOA, PFBS, PFNA, and PFHxS presence (i.e., PFAS associated with the AOPI).”

Let’s examine the Army’s reasoning error, its analytical failure, its faulty premise.

Logical Lapse #1: Depth to groundwater is treated

as a reason not to investigate.

The Preliminary Assessment / Site Inspection excludes groundwater sampling at Tripler Army Medical Center on the grounds that groundwater is estimated to be 200 feet below ground surface, as though depth itself were a protective barrier.

The State of Hawaii’s Commission on Water Resource Management operates a network of deep monitor wells to track aquifer health. These specialized wells often exceed 1,000 feet in depth.

Under CERCLA, the question is not whether groundwater is shallow or deep, but whether it is a plausible receptor—and at a major medical center on Oʻahu, above a sole-source aquifer, it unquestionably is.

PFAS compounds are persistent, highly mobile, and known to migrate vertically through fractured rock, utility corridors, and disturbed subsurface soils common to long-active installations. Treating depth as evidence of safety is not a scientific conclusion; It’s a way to save a buck. They know better.

Logical Lapse #2: Unknown stormwater pathways

are used to justify not looking off-site.

The PA/SI says that the stormwater sewer route and discharge location for Fire Station #3 are unknown, then uses that lack of knowledge to justify excluding off-installation surface water and sediment sampling. This reverses basic environmental logic. When discharge pathways are uncertain, the risk is greater, not smaller, because contaminants may already be leaving the installation uncontrolled.

Unknown outfalls are precisely the locations where downstream sampling is warranted. We must determine where contaminants are going and who may be affected. The unborn child carried by an unsuspecting mom in housing adjacent to an Army base may be endangered.

Ignorance of the pathway does not negate exposure; it heightens the obligation to investigate it.

Finally, the PA/SI says that the stormwater sewer route and discharge location for Fire Station #3 are unknown, although this could be very easily established.

Logical Lapse #3: Soil sampling is misrepresented as a substitute for exposure assessment.

The Preliminary Assessment / Site Inspection: asserts that soil sampling alone can “more accurately evaluate” PFAS presence associated with the area of potential interest, effectively treating soil as the primary endpoint of contamination.

This statement demonstrates a profound mischaracterization of PFAS behavior. Soil sampling can confirm that a release occurred, but PFAS are water-soluble, migratory chemicals that move into stormwater systems, leach downward to groundwater, and accumulate in surface water, sediments, and biota. Without groundwater, surface water, or sediment sampling, soil data cannot evaluate transport, exposure, or risk. Presenting soil as a comprehensive metric does not serve science.

The Army took five soil samples from 0 to 2 feet below the ground at locations near the firehouse. PFOS exceeded the Office of the Secretary of Defense residential risk screening level in one sample, so the site moves ahead in the CERCLA process.

The Army failed to collect a single groundwater or surface water sample anywhere on the installation. Few are paying attention. The media isn’t reporting on these stories. The Army is off the hook. O’ahu is in trouble.

Sewer System

Rather than methodically testing sewer outflows and taking responsibility for carcinogenic materials leaving Tripler Army Medical Center, the Army attempts to reassure the public that municipal treatment facilities can satisfactorily manage the contamination. This assertion sidesteps established scientific evidence showing that conventional wastewater treatment does not destroy PFAS, but instead redistributes the toxins into effluent, sludge, air emissions, and landfills.

From the PA/SI – “There are four sewer and industrial waste lines, out of which two are for sanitary sewer, one for industrial waste sewer, and one for storm water. Tripler Army Medical Center drains the sanitary sewer to the municipal wastewater treatment plant (WWTP) at Sand Island. Sludge from the WWTP at Sand Island has historically either been incinerated at 1400 to 1500 degrees Fahrenheit and/or disposed at Waimanalo Gulch Landfill.”

The Army offers these disposal pathways as reassurance, yet neither incineration at these temperatures nor landfill disposal has been demonstrated to reliably and completely destroy PFAS. Rather than eliminating the chemicals, these processes transfer PFAS from Tripler Army Medical Center into Hawaiʻi’s air, soil, and water, shifting responsibility downstream while avoiding direct scrutiny of releases originating at the medical center itself.

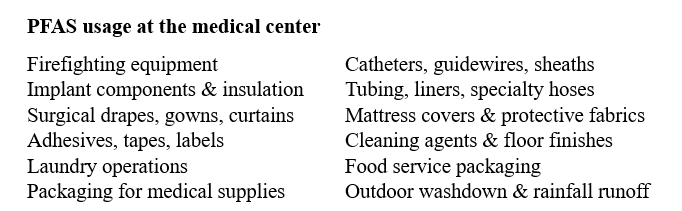

Tripler Army Medical Center uses hundreds of PFAS-containing products every day—not just firefighting foam! These materials exit the installation through wastewater, trash, regulated medical waste, and stormwater. Yet the Site Inspection sampled only soil at the fire station while excluding groundwater, surface water, sediment, sludge, ash, and air—precisely the media where PFAS are known to accumulate and migrate.

Laundry operations are likely the number one source of PFAS release. Surgical drapes, gowns, curtains, and mattress covers often contain high levels of PFAS. The carcinogens may escape in the laundry, or they may enter the environment through landfilling or incineration when the items are discarded. PFAS never go away. They just move from place to place and threaten human life as they move around.

The Army is capable of removing a substantial portion of PFAS from the Tripler Army Medical Center waste stream, yet it has chosen not to do so. This reflects an entrenched institutional mindset that prioritizes downstream disposal over source control. This mindset must be confronted and changed.

This is the 6th part of a multi-part series..

Part 1 – The Army is leaving contaminated O’ahu sites to focus on Pohakuloa

Part 2 – PFAS contamination at Pohakuloa

Part 3 – PFAS contamination at three leased bases on O’ahu

Part 4 – PFAS contamination at Wheeler Army Airfield

Part 5 - PFAS contamination at the Fort Shafter Hawai’i Child Development Center

This project is supported by financial assistance from the Sierra Club of Hawaii.

Please consider donating to the Sierra Club of Hawai’i. Your donation will continue efforts to achieve Hawaiʻi’s 100% renewable energy goal, defend our oceans and forests, and build a more self-reliant and resilient community that prioritizes justice, enhances natural and cultural resources, and protects public health over corporate profit. Donate Here.