The Army shows no progress on cleaning up PFAS in Hawai’i

CERCLA Has Become a Procedural Stumbling Block

By Pat Elder

February 17, 2026

PFAS doesn’t fit into the CERCLA process.

For decades, the U.S. Army and the Hawaii Army National Guard have used per- and polyfluoroalkyl substances (PFAS) across many, if not all of the active Army installations and 4 Hawai’i Army National Guard bases across the state. The Army has failed to adequately track, report, or clean up toxic PFAS releases into the environment.

These “forever chemicals,” linked to cancer, immune dysfunction, and developmental harm, persist in soil, water, air, and living organisms long after their use has ended.

This investigative series documents the military’s PFAS use and disposal practices in Hawaiʻi, and the striking gaps in its own reporting. It reveals a pattern of narrow inquiries, selective testing, and disposal strategies that move contamination offsite, only to plague communities elsewhere..

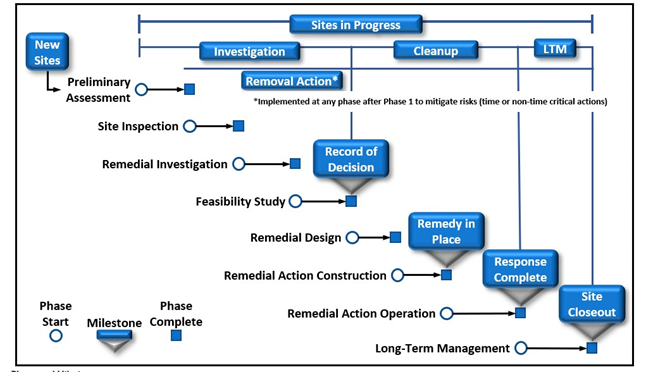

The CERCLA Process

PFAS contamination on military installations is intended to be addressed under the Comprehensive Environmental Response, Compensation, and Liability Act of 1980, (CERCLA). It doesn’t work.

CERCLA was enacted 46 years ago to address solvents, petroleum, and other degradable industrial pollutants — not ultra-persistent PFAS compounds that resist breakdown and defy conventional cleanup methods.

CERCLA was enacted in 1980 to address releases of hazardous substances at contaminated sites, including chlorinated solvents such as trichloroethylene (TCE) and perchloroethylene (PCE), and heavy metals like lead, chromium, and arsenic.

Over the decades, established cleanup technologies have evolved to manage these contaminants through excavation, stabilization, containment, pump-and-treat, soil vapor extraction, and engineered biodegradation or oxidation. These methods assume pollutants can be destroyed, removed, transformed, or reduced to regulatory standards within measurable timeframes.

That assumption collapses when applied to PFAS, a reality many are reluctant to confront while entrenched interests profit from the status quo.

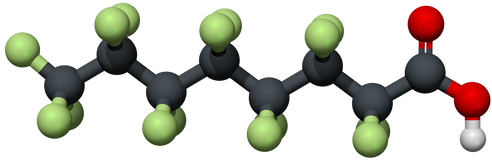

A PFOS molecule is shown here. Per Fluoro Octane Sulfonic acid is a killer.

Per-and poly Fluoro Alkyle Substances, (PFAS) are in a league of their own. They are super-persistent, highly mobile, bioaccumulative, fluorinated compounds that do not meaningfully degrade under environmental conditions and lack proven, scalable destruction technologies in soil and groundwater. There are more than 16,000 kinds of PFAS today.

While many PFAS precursors do transform over time, the process typically results in the formation of highly stable terminal perfluoroalkyl acids like PFOS, PFHxS, and PFOA—compounds that are even more persistent and more bioaccumulative! In other words, the environmental transformation of PFAS works against us. It turns unstable precursors into persistent terminal contaminants.

The CERCLA framework assumes that contaminants can be contained and ultimately remediated to protective levels. With PFAS, most “remedies” amount to wish lists consisting of partial hydraulic control, media transfer, or off-site “disposal.” This is tantamount to moving contamination around, rather than eliminating it. Calling this a “cleanup” process is dishonest.

The concern is not simply whether CERCLA can be applied to PFAS, but whether the Department of Defense is spending billions on preliminary investigations based on the assumption that an endgame exists. It does not.

For PFAS, destructive technologies remain largely unproven, especially at scale. It seems that exciting technologies pop up every few weeks! They work well in laboratory settings, but the scale of the problem is overwhelming because PFAS travel vast distances and remain highly carcinogenic in groundwater, surface water, sediment, and air, To further confuse matters, regulatory thresholds ebb and flow like the contaminated waters flowing from military bases that coat the banks of streams and rivers with layers of PFAS.

Prometheus stole fire from the gods to advance humankind. This gift proved both transformative and ruinous. The analogy cuts to the heart of the intellectual dishonesty embedded in our regulatory response to PFAS.

We must develop a strategy that is honest about long-term stewardship because elimination is not feasible, and we must recognize that manufacturing these monsters is criminal in the first place. Only a small percentage of products containing PFAS or applications using PFAS are irreplaceable. We must regulate them and keep these compounds out of the waste stream.

In the meantime, we must develop PFAS replacement technologies, particularly alternatives to fluoropolymer-based materials used in high-frequency, high-performance printed circuit boards. This must become the next high-tech Wall Street frontier. The same carbon-fluorine chemistry that enables advanced electronics also creates environmental persistence we cannot ignore.

DOD fixation on groundwater

Increasingly, science is confronting a difficult reality: reducing PFAS source concentrations to meet emerging maximum contaminant levels in groundwater requires treatment methods that don’t exist in the field! Since 2017, the Department of Defense has spent approximately $2.6 billion under CERCLA investigating PFAS contamination, with projected future costs exceeding $9 billion more in the coming years. Yet there remains no clear engineering consensus on what “cleanup” looks like.

Although the DoD concentrates on groundwater and drinking water contamination from its firefighting foams, that captures only part of the threat. PFAS pollute surface water, sediment, soil, subsurface soils, and indoor and outdoor air, while infiltrating the food web and the life it sustains. The exposure pathways are far broader than the narrow lens through which the military chooses to view them.

The military continues to advance projects without a demonstrated endgame for eliminating the deadly compounds it has unleashed throughout the archipelago. PFAS shatters the fundamental assumption of the Polluter Pays Principle: that the harm is finite and fixable.

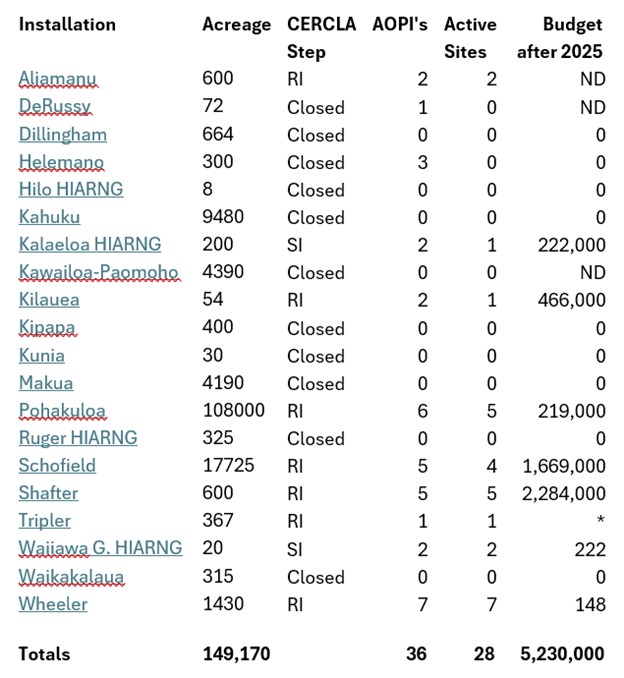

The Army has shut down the CERCLA process regarding PFAS at 11 of the 20 Army installations in Hawaii

largely without public notice or scrutiny.

Under CERCLA, a Preliminary Assessment is largely a paper-based screening that relies on existing records, interviews, and reconnaissance that can either terminate further action or identify “Areas of Potential Interest, (AOPIs)” to be carried forward. A Site Inspection then involves targeted field work and environmental sampling at those areas to confirm contamination, evaluate potential exposure pathways, and determine whether the site should advance to a full remedial investigation.

See the DOD report, Progress at 723 installations being assessed for PFAS, 2025. The DoD reports that “progress” is being made at the 723 installations being assessed for PFAS use or potential release across the country. A closer look provides insight into how poorly the CERCLA process is being implemented in Hawaii.

Army - All HI Installations - CERCLA Investigations

RI - Site proceeds to Remedial Investigation

Closed - PFAS investigation is complete.

SI - Site Inspection

AOPI's - Areas of potential interest

ND - No data on DOD PFAS Progress Report

* - Tripler & Shafter share the same budgeted item

DOD can’t keep track of it all

The DOD cannot accurately keep track of the ongoing CERCLA PFAS investigations at all of the 20 Army installations in Hawaii and across the country. The DOD report, “Progress at the 723 installations being assessed for PFAS use or potential release”, March, 2025, lists 17 Army bases in Hawaii. The DOD omitted Aliamanu Military Reservation, the Kawailoa–Poamoho Training Area and Fort DeRussy from its accounting. Because Fort Shafter and Tripler Army Medical Center are listed together, we can’t tell how much of the $2,284,000 listed as planned obligations after 2025 pertain to each facility. In the scope of things, it’s a paltry figure.

In Hawaiʻi, all 20 Army installations have passed through the PFAS Preliminary Assessment/Site Inspection (PA/SI) process. The installations contain a total of 149,170 acres. A total of 36 areas of potential interest, or AOPI’s as the Army prefers to call them, were initially identified. Of these, 8 were eliminated, leaving 28 active CERCLA sites to be further investigated. Of these, all except for one is associated with the use of aqueous film-forming foam, (AFFF). The other was, surprisingly, a metal plating shop at Fort Shafter.

Although the Army would have us believe otherwise, PFAS contamination is not limited to AFFF releases at fire training areas. PFAS are routinely used in metal plating operations, engine maintenance chemicals and lubricants, wastewater treatment systems, laundry facilities, landfills, sludge disposal, and stormwater infrastructure. These are chronic, active release pathways. Waste streams, biosolids, landfill leachate, and airborne dust move PFAS beyond their points of use and into surrounding soil, groundwater, and surface waters. The Army’s investigations have focused on firefighting foam, ignoring the broader operational footprint through which PFAS enter the environment.

Following is a list of 11 Army installations in Hawaii where the CERCLA process for PFAS investigation and remediation is permanently shut down: DeRussy, Dillingham, Helemano, Hilo HIARNG, Kahuku, Kawailoa-Paomoho, Kipapa, Kunia, Makua, Ruger, and Waikakalaua.

The Army has identified nine installations encompassing 28 Areas of Potential Interest. Twenty-seven of the 28 involve the documented use of aqueous film-forming foam (AFFF), a well-known source of PFAS contamination. By limiting its investigation almost exclusively to AFFF release sites, the Army ignores a broader universe of PFAS sources that result in chronic, diffuse releases of PFAS into soil, groundwater, and surface water.

The narrow framing of inquiry understates the true scope of contamination.

Aliamanu (2)

AFFF - Vehicle Fire Location;

AFFF- Former Fire Station #6

Kalaeloa HIARNG (2)

AFFF use at Former HDOT Fuel Farm Area;

AFFF Hangar Suppression System and Storage

Kilauea (1)

AFFF - Building 59: Fire Station #1

Pohakuloa (5)

AFFF- Building 39: Former Fire Station;

AFFF- Building 390: Fire Station;

AFFF- Current and Former Fire-Training;

AFFF - Former Aqueous Film-Forming Foam Training Area;

AFFF - Bradshaw Army Airfield Runway

Schofield (4)

AFFF- Building 494: Former Fire Station #15;

AFFF- Former Pumper Certification Location

AFFF - Former Training Area

AFFF - Building 140: Fire Station #15

Shafter (5)

AFFF- AFFF Training Area

AFFF- Canal Car Accident

AFFF- Parking Lot Fires

AFFF- Building 322 Fire Station #3

Building 1507- Wing A: Former Metal Plating Shop

Tripler (1)

AFFF- Building 320: Fire Station #3

Waiiawa Gulch HIARNG (2)

AFFF- Firetruck Pump Test Area

AFFF- Vehicle Maintenance Facility and Firetruck Area

Wheeler (7)

AFFF- Building 200: Fire Station #14

AFFF- Fire Truck Water Tank Drainage Area

AFFF- Building 100: Car Fire

AFFF Training Area

AFFF- Helicopter Crash

AFFF- Wheeler Gulch

AFFF- Building 251: Civil Air Patrol Hangar

=========================

Although both the Active Army and the Hawaiʻi Army National Guard operate under CERCLA authority, their nomenclature often reflects different program structures and levels of commitment. Active Army installations typically move from the Preliminary Assessment and Site Inspection into a Remedial Investigation once a release is confirmed.

By contrast, National Guard facilities, operating through the National Guard Bureau’s restoration program, often remain labeled in the PA/SI or “Site Investigation” phase for longer periods. A site Inspection asks whether contamination warrants further action, whereas a remedial investigation assumes that it does.

While environmental investigations and cleanup activities are largely funded by the federal government through the National Guard Bureau, day-to-day operational authority over Hawaiʻi Army National Guard facilities rests with the Governor of Hawaiʻi. The federal government pays for restoration work, but the installations operate under state command. In the context of CERCLA, this can affect oversight, reporting pathways, and the pace at which investigations advance from preliminary assessments and site inspections into formally designated remedial investigations.

This is the seventh article in a series examining PFAS contamination at military facilities across Hawaiʻi. Next, we will calculate what it would actually cost the Army to implement a scientifically defensible PFAS testing regime at Schofield Barracks — not the narrow, minimalist sampling currently underway, but comprehensive soil, groundwater, surface water, sediment, and precursor analysis.

We will then expand that analysis to other Army installations in the state. Finally, we will estimate the true cost of attempting to “clean up” PFAS contamination — through pump-and-treat systems, soil excavation and off-site disposal, high-temperature destruction, and shipment to licensed facilities on the mainland. The numbers will illuminate what the Army avoids discussing: the scale of the liability.

Part 1 – The Army is leaving contaminated O’ahu sites to focus on Pohakuloa

A look at the Army’s strategy for retaining lands in Hawai’i while public pressure is mounting to not renew Army-leased lands 38 pages. January 12, 2026.

Part 2 – PFAS contamination at Pohakuloa

PFAS is much worse at Pohakuloa than anyone knew, while it has not been discussed in negotiations between the Army and the state. 27 pages. January 14, 2026.

Part 3 – PFAS contamination at three leased bases on O’ahu

The Army says there is no PFAS contamination at Kahuku Training Area, Makua Military Reservation, and Kawailoa-Poamoho Training Area but an analysis shows otherwise. 27 pages. January 26, 2026

Part 4 – PFAS contamination at Wheeler Army Airfield

Pleany of evidence showing how the Army flagrantly violates federal law. It reports 174.7 parts per trillion of PFAS from one groundwater test while the Navy reports 2.88 million parts per trillion in groundwater nearby. February 1, 2026. 33 pages. Feburary 1, 2026

Part 5 - PFAS contamination at the Fort Shafter Child Development Center

The daycare facility is located 300 feet from a contaminated former Army firefighting foam training area. A stream believed to be carrying the carcinogens passes just 60 feet from where children play outside. 10 pages. February 7, 2026

Part 6 - PFAS contamination at Tripler Army Medical Center

The Army hides PFAS contamination from dozens of sources, refusing to divulge levels of the toxins in the environment. 7 pages. February 8, 2026

This project is supported by financial assistance from the Sierra Club of Hawaii.

The Sierra Club of Hawaiʻi is the state chapter of the national Sierra Club and operates as a grassroots environmental advocacy organization focused on climate, land, water, justice, and outdoor access issues in Hawaiʻi. Can you take a moment to support this work? Please donate.